This week brings another in my series on people whose blogs and other writings are worth reading. (The first post was on the libertarian economist Arnold Kling.) I try to highlight people who aren’t household names but have something worth saying, enough so that I keep track of what they’re up to ib regular. This week’s person, the Russian ecologist turned American historian Peter Turchin, was name-checked in a Paul Krugman column recently, and he’s attracting more attention. However there’s still time to get in on the ground floor (as it were) by following his blogging at the Social Evolution Forum (a group blog, but Turchin does most of the posts).

Turchin’s big topic is cliodynamics, “the new transdisciplinary area of research at the intersection of historical macrosociology, economic history/cliometrics, mathematical modeling of long-term social processes, and the construction and analysis of historical databases.” The idea that human history moves in cycles is a very old one; what is new about the approach of Turchin and other like-minded researchers is their attempt to mathematically model these cycles, using techniques similar to those used for modeling the dynamics of biological ecosystems. Given the lack of good data about historical trends this can be a challenge, but the results are interesting enough for me to look forward to seeing where the discipline goes from here.  One area where Turchin has some interesting things to say is American history, specifically his idea that demographics and other factors have driven what he calls the “double helix of inequality and well-being.” The general idea, outlined in an Aeon Magazine article and accompanying blog post, is that “general well-being (that is, of the overwhelming majority of population) tends to move in the opposite direction from inequality: when inequality grows, well-being declines, and vice versa.” Here Turchin measures well-being using an index of four variables (one being age at marriage, on the theory that pessimistic people tend to marry later) and inequality using the ratio of the wealth of the richest Americans to the median wealth (i.e., 50% of Americans have more wealth, 50% less).

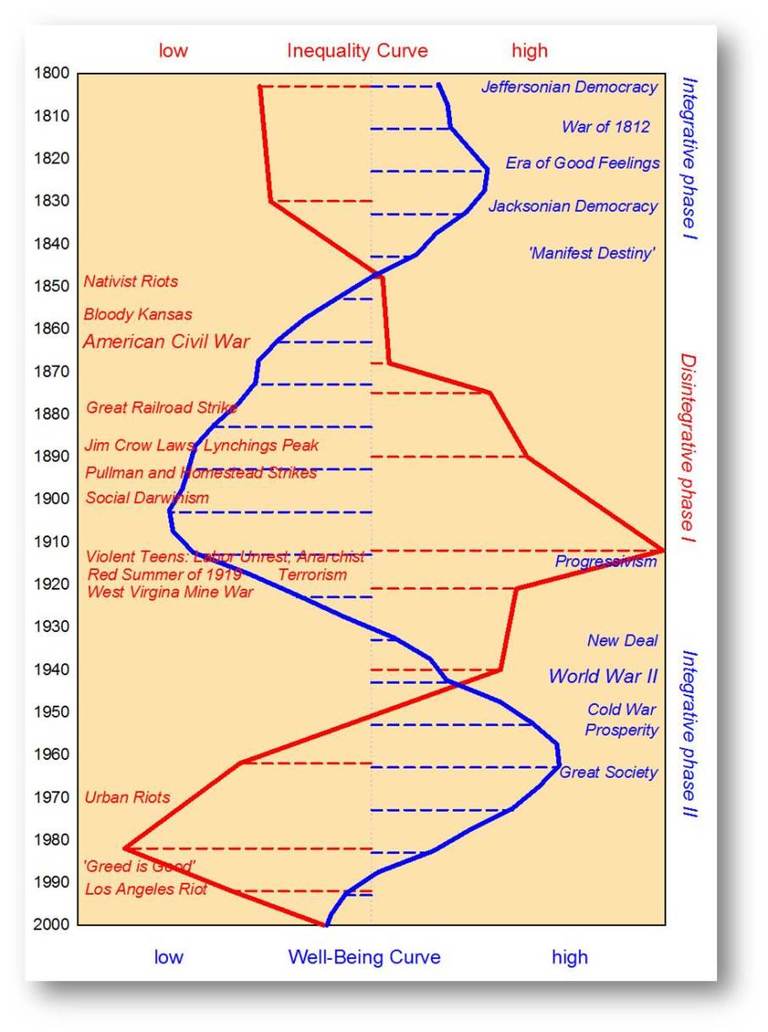

One area where Turchin has some interesting things to say is American history, specifically his idea that demographics and other factors have driven what he calls the “double helix of inequality and well-being.” The general idea, outlined in an Aeon Magazine article and accompanying blog post, is that “general well-being (that is, of the overwhelming majority of population) tends to move in the opposite direction from inequality: when inequality grows, well-being declines, and vice versa.” Here Turchin measures well-being using an index of four variables (one being age at marriage, on the theory that pessimistic people tend to marry later) and inequality using the ratio of the wealth of the richest Americans to the median wealth (i.e., 50% of Americans have more wealth, 50% less).

Turchin notes that these indices move opposite to each other (i.e., times of low inequality are times of higher well-bring, and vice versa), not necessarily because one directly causes the other but (in Turchin’s view) because both reflect an underlying dynamical system driven by several factors: the supply of labor, returns to business owners and managers, political competition among the economic elites (due to what Turchin calls “elite overproduction”), changes in social norms, and so on.1 Turchin is working on a book, A Structural-Demographic Analysis of American History, to explain and justify his theory in more detail; although the book hasn’t been published yet, he’s made a draft available online if you want to check it out.2

No scientific theory worthy of the name is complete without making some predictions (or, as Turchin calls it in this case, a projection). Turchin went out on a limb and made a major one three years ago in a letter [PDF] published in the magazine Nature:

In the United States, we have stagnating or declining real wages, a growing gap between rich and poor, overproduction of young graduates with advanced degrees, and exploding public debt. . . . Historically, such developments have served as leading indicators of looming political instability. . . . In the United States, 50-year instability spikes occurred around 1870, 1920 and 1970, so another could be due around 2020.

For a quick overview of why Turchin thinks 2020 is the likely timeframe, see the 2013 Aeon article referenced above, the slides [PPT] for a presentation he gave in 2011, or (if you have a bit more time) his 2012 paper “Dynamics of political instability in the United States, 1780–2010” [PDF].

Even if Turchin’s theory is valid, it’s not going to be so precise as to be able to make predictions down to the exact year. The theory is also silent on exactly how such an “instability spike” might manifest itself. But it is intriguing to think about what might be happening in the US around the time President Clinton or President Christie runs for re-election, if present trends continue.

In one of Turchin’s most interesting series of blog posts, he considered the legal minimum wage not as something that has or had any major economic impact, but rather as an indicator of changing social norms—roughly speaking, a measure of society’s general opinion as to what the least skilled workers deserve for their labor. ↩︎

Turchin is a strong supporter of scientists publishing in open access journals, and makes a lot of his work available online. This includes his earlier book Secular Cycles as well as complete issues of the journal he founded, Cliodynamics: The Journal of Theoretical and Mathematical History. ↩︎