Wooden pickets at the rear of the Chrysalis, forming guard rails for the stage. (Click for a higher-resolution version.) The perforated aluminum sheets in the background cover and protect the ZEPPS panels closest to the stage floor. Image © 2017 Living Design Lab; used with permission.

tl;dr: Getting the details right on the Chrysalis, featuring Living Design Lab and Mahan Rykiel Associates.

This article is one in a series exploring in depth the creation of the Chrysalis amphitheater in Merriweather Park at Symphony Woods in Columbia, Maryland. For the complete list of articles please see the introduction to the series.

Previous articles in this series discussed the design, fabrication and installation of the steel frame and skin of the Chrysalis, as well as the construction of the “subfloor” to which the steel frame is attached. This article completes that discussion, focusing on various details of the Chrysalis design and construction not previously covered. It features the work of Living Design Lab, architect for the Chrysalis, and Mahan Rykiel Associates, the landscape architect.

The wooden boardwalk and ramp leading to the Chrysalis stage. (Click for a higher-resolution version.) The boardwalk abuts the clay pavers in front of the stage where the traffic cones are placed. Image © 2017 Inner Arbor Trust; used with permission.

Living Design Lab

The “Chrysalis Team” page on the merriweatherpark.org web site includes a number of people and companies previously discussed in this series, including Marc Fornes and THEVERYMANY, Arup, Zahner, and Whiting-Turner. Right near the top of the list you’ll find listed Living Design Lab as architect.

To quote Wikipedia, an architect “plans, designs, and reviews the construction of buildings.” Whether or not there’s a separate designer on the project (as there was for the Chrysalis), ultimately the architect is responsible for the project being able to meet the needs of the people who are going to use it.

As noted above, for the Chrysalis the Inner Arbor Trust chose as architect Living Design Lab, a Baltimore firm founded in 2014 by Davin Hong, subsequently joined by Kevin Day. The principals of Living Design Lab have shown a willingness to stretch themselves, to take on complex and ambitious projects with multiple stakeholders, to practice design above the level of a isolated building or structure, and to do work that serves the community as a whole and not just their client.

Projects on which they’ve worked include advocacy for an integrated design approach to renewing Baltimore’s schools and their surrounding neighborhoods, a project to revitalize Greenmount Avenue in Baltimore, the Baltimore Green Network—an ambitious plan to create an interconnected system of greenspaces throught the city—and a project to build cities for refugees in the Middle East in place of their current camps.

This background prepared Living Design Lab to play a key role in the complex and ambitious project that was the Chrysalis, working with THEVERYMANY, Arup, and Zahner to take the formal concept of the Chrysalis—the 3-dimensional form created through the parametric design process—and make a buildable structure able to handle the demands to be placed upon it.

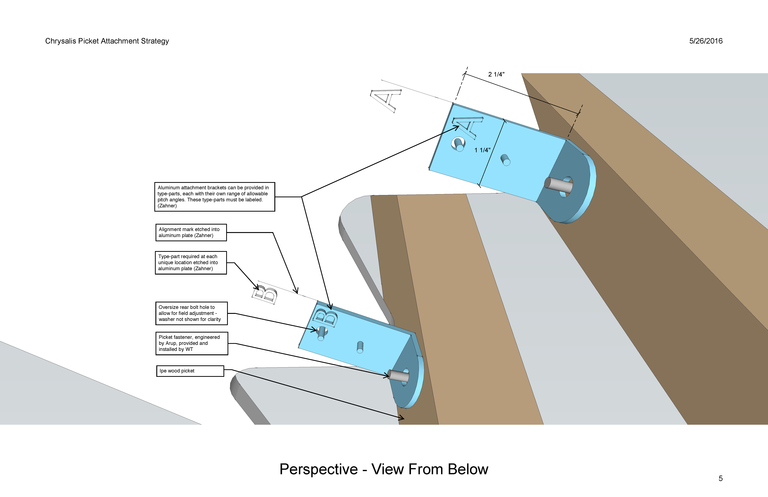

A rendering showing the wooden pickets, the brackets by which they are attached, and the aluminum support plate to which the brackets are attached. (Click for a higher-resolution version.) Image © 2014 Inner Arbor Trust; used with permission.

Sweating the details

Even a typical architectural project involves a myriad of details, more or less visible to the people using it. Less visible details include those needed to satisfy local authorities that a building or other structure will be safe for people and satisfy other requirements: Does it provide adequate fire protection? Does it comply with ADA requirements regarding access? What about handling of storm water runoff? And so on . . .

Even the more visible details often go unnoticed by many, but can elicit a sense of delight when done really well, or irritation when done poorly—think of how satisfied we feel when we hold and use a really well-designed smartphone, for example, or how we’re annoyed when we pay thousands for a new car only to find that the body panels aren’t consistently joined, or that an otherwise sumptuous interior is spoiled by misplaced controls and cheap plastic parts. And of course we want good design for an reasonable price.

For the Chrysalis Living Design Lab dealt with both types of details, working to understand and satisfy a myriad of technical requirements related to the function, construction, cost, schedule, and regulatory approval of the Chrysalis, all without compromising the design intent. For example, consider the question of fire protection: Above the stage floor the Chrysalis is a pure metal structure of steel and aluminum. Arguably a conventional building sprinkler system is neither necessary nor appropriate for the Chrysalis—just one of the many issues that had to be negotiated with Howard County officials for a structure very different than those that typically come before them.

Previous articles have discussed various strategies employed to preserve the design intent for the Chrysalis—so often compromised in projects—while making it possible for it to fulfill its purposes, including most notably serving as a professional performance stage. These strategies included the introduction of the steel framework with its “spine” of primary steel and “ribs” of secondary steel to support heavy theatrical loads and resist dynamic wind loads, and the use of ZEPPS panels to support the pleated surface of aluminum shingles.

This attention to design intent and the uniqueness of the Chrysalis extended to other aspects as well. To explore just one, consider the wooden pickets attached to the exterior of the Chrysalis subfloor (see the first figure above). These pickets are Living Design Lab’s elegant solution to three separate problems:

First, code requirements dictate that there be adequate protection to prevent people from falling off the stage and other surfaces greater than a certain height above the ground. Second, aesthetic considerations dictate that some sort of screening be provided for the otherwise uninterrupted expanses of concrete forming the exterior walls of the subfloor. Finally, budget considerations mean that any solution must not be overly expensive to fabricate and install.

The solution that Living Design Lab came up with was to use vertical wooden pickets (of the same ipe hardwood used for the stage floor) extending from the ground either to the stage floor (at the front of the stage) or beyond it (at the rear of the stage) to form guard rails. The result is more aesthetically pleasing than using conventional railings for the stage and a separate screen or facade for the exterior walls.

But how to build and install these wooden pickets, given that they have to both follow the curve of the stage floor and also match up with the angled legs of the Chrysalis at the points where the guard rails meet the legs? Every picket might have a different orientation in 3-dimensional space, and thus have to be attached in a slightly different way.

For the solution to the problem see the rendering above: Each picket is attached to a angled aluminum attachment bracket. Different attachment brackets have different angles, so that their respective pickets can assume different angles to the ground depending on the degree to which the underlying subfloor wall “leans in.” (Viewing the picket from above and comparing it to an airplane, this is the “pitch” angle.)

Each picket is free to rotate around the bolt attaching it to its bracket, so it can also be slanted to the left or right in a direction parallel to the exterior subfloor wall—in airplane terms, the “roll” angle of the picket can change. Finally, the bracket itself is attached to a horizontal aluminum support plate in such a way that the bracket and its attached picket can “yaw” back and forth slightly to match the curve of the stage floor and the positions of its neighboring pickets.

This arrangement of pickets, brackets, and support plates, elegant as it is, would be too expensive to fabricate if each bracket had to be unique, and too complicated to install as well, given the need to adjust the pickets to precise angles. To address this, the system was designed to require only a limited number of types of brackets, each holding a picket to a particular angle to the ground. The underside of each support plate was then marked to indicate to the installers the type of bracket to be used at each position, together with a line to indicate how the installer should align each bracket relative to the plate (the “yaw” angle).

This system is but one example where having a balance of technical expertise with design sophistication enabled Living Design Lab and the other members of the core Chrysalis team to realize the form of the Chrysalis as a buildable design within a reasonable budget and time schedule.

Pervious clay pavers forming the pedestrian area in front of the Chrysalis stage. (Click for a higher-resolution version.) To the upper right is the walkable access road leading to the Chrysalis from the Merriweather Post Pavilion VIP parking lot. In the background is the beta stage. (See also the figure below.) Image © 2017 Inner Arbor Trust; used with permission.

Mahan Rykiel Associates

While Living Design Lab is a relatively new firm, Mahan Rykiel Associates has been a fixture of the Baltimore scene for over 30 years. Founded by Catherine Mahan in 1983 as Catherine Mahan Associates, it became Mahan Rykiel Associates after Scott Rykiel joined the firm in 1993 and became a partner with Mahan.

Mahan Rykiel has completed or is currently working on a host of projects in the Baltimore-Washington region, including several involving parks: Harbor Point on the waterfront west of Fells Point, Pierce’s Park next to the Columbus Center at the Inner Harbor, Eager Park north of Johns Hopkins University, and Fern Valley and the National Capitol Columns at the US National Arboretum.

Closer to home, Mahan Rykiel has many associations with Columbia: Scott Rykiel used to work at the Columbia-based firm LDR International, two partners at the firm currently live in Columbia, and Mahan Rykiel has been involved with downtown Columbia projects for over ten years, including being the landscape architect for the Columbia Association’s Symphony Woods Park project.

After the Columbia Association decided to adopt the Inner Arbor plan and created the Inner Arbor Trust to carry it out, the Trust decided to take advantage of Mahan Rykiel’s deep knowledge of Symphony Woods and added them to the design team for Merriweather Park at Symphony Woods.

The accessible path leading to the Chrysalis. (Click for a higher-resolution version.) The view is looking up the hill from the alpha stage to the Merriweather Post Pavilion VIP parking lot. Image © 2017 Inner Arbor Trust; used with permission.

Getting to and from the Chrysalis

In joining the Inner Arbor design team one major task Mahan Rykiel took on was that of creating a new path system for Symphony Woods—fulfilling the mandate of the Howard County Planning Board to minimize tree removal by “aligning paths around healthy trees and minimizing grading.” Mahan Rykiel’s work at the Chrysalis represents the beginning of creating a comprehensive system of meandering paths for Merriweather Park at Symphony Woods, as seen in the multiple pedestrian areas around the structure.

The first is an 8-foot-wide accessible path leading to the Chrysalis from a set of seven new handicap parking spaces at the Merriweather VIP parking lot. This path winds around the existing Merriweather Post Pavilion administrative offices and concludes in front of the Chrysalis between the alpha and beta stages.

In order to minimize the slope of the accessible path it goes below grade a bit for one section, in which it is flanked by low walls made of natural stone from the region. To minimize storm water runoff the accessible path features flexible pervious pavement made from recycled tire granules, aggregate rock, and a binding agent. (See the figure above.)

At the Chrysalis the accessible path terminates in a pedestrian area in front of the alpha and beta stages. This area uses light-colored pervious clay pavers, again to minimize storm water runoff. (See the figure above.)

At the south end of the Chrysalis concrete and wooden steps lead to the beta stage. At the north end of the Chrysalis the clay pavers transition to a wooden ramp that provides an accessible approach to the alpha stage floor. This ramp is surfaced with the same ipe hardwood used for the Chrysalis stage floor, and flanked by the same wooden picket discussed above, serving as guard rails. (See the figure above.)

At present this elevated wooden boardwalk is relatively short. However, in phase 2 of the development of Merriweather Park at Symphony Woods the boardwalk will be extended west and then northeast to provide an accessible path to the Chrysalis from a new entrance to the park at the corner of Little Patuxent Parkway and South Entrance Road, next to the multi-use pathway to Lake Kittamaqundi.

The final approach to the Chrysalis is via a short access road providing vehicular access to the loading dock at the rear of the alpha stage. Paved with asphalt and edged with cobblestones, this road provides another walkable approach to the Chrysalis.

Supplemented by landscaping work around the Chrysalis to restore a more natural landscape, the Chrysalis path system and the other areas surrounding the Chrysalis represent Merriweather Park at Symphony Woods in miniature, foreshadowing how Mahan Rykiel’s work will enhance Symphony Woods during the subsequent phases of park development.

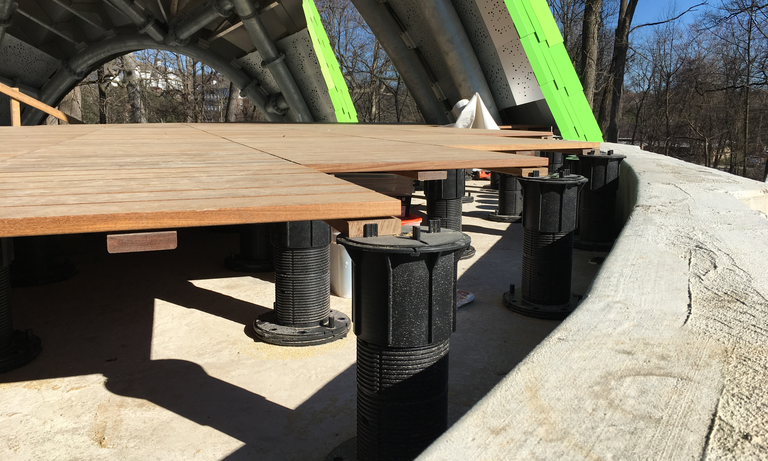

The stage floor of the Chrysalis in the process of being installed. (Click for a higher-resolution version.) The black cylinders are Bison adjustable deck supports, each holding up one corner of four adjacent wooden tiles. Image © 2017 Frank Hecker; available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Taking the stage

Another key element of the Chrysalis in its final form, important to performers and audience alike, is the stage floor.

This floor has to satisfy several requirements: it has to provide as level a surface as possible; bear the weight of performers, their equipment, and an on-stage audience that might number in the hundreds; be yielding enough for dance and related performances; be sturdy enough to last a long time while exposed to the elements; provide adequate space for electrical cabling and other below-stage equipment; allow for easy repair if damaged; and, finally, be installable above a concrete surface that may be somewhat uneven in places.

The path to a solution began with Michael McCall, the president of the Inner Arbor Trust: in the course of planning a deck for his own home, McCall came across the Bison system of wooden floor tiles and adjustable deck supports. (See the figure above.) Living Design Lab and Arup evaluated the system, and based on its multiple advantages the Chrysalis team decided to adopt it for the main stage floor.

Each Bison unit supports the corners of four adjacent wooden tiles. The deck supports are threaded to allow fine adjustments to be made to the height of the tiles to make the stage floor as level as possible. If needed the base of each unit can also be adjusted to compensate for the underlying surface sloping somewhat.

The wooden tiles for the floor are 2-foot by 2-foot and (like the wooden pickets and the ramp to the Chrysalis) are made of ipe hardwood. They are elevated several inches above the underlying concrete subfloor to allow space for electrical cabling and other equipment, and can be individually removed if needed to gain access to the space under the stage floor. They can also be individually replaced if damaged.

The Inner Arbor Trust also took advantage of the nature of the tiles to mount a fundraising campaign, allowing people or organizations to have their names or other texts laser-engraved on the individual planks of the tiles in return for donations. The final form of the Chrysalis stage floor thus reflects not only the contributions of Living Design Lab, Arup, and the other members of the Chrysalis team, but also the contributions of the many other people and organizations who have helped bring the Chrysalis to life.

The Chrysalis stage floor as installed, with engraved wooden tiles. (Click for a higher-resolution version.) Image © 2017 Howard County, Maryland.

For further exploration

This article is based on material from a variety of sources, including the following:

For more on Living Design Lab and its principals, Davin Hong and Kevin Day, see the following:

- Living Design Lab. The firm’s web site.

- Davin Hong. Professional biography of Davin Hong.

- Kevin Day. Professional biography of Kevin Day.

- “Building communities through schools: An interview with Davin Hong. A 2013 interview with Davin Hong.

For more on Mahan Rykiel Associates, see the following:

- Mahan Rykiel Associates/Practice. About page on the Mahan Rykiel site.

- “Moving heaven & earth,” by Stephanie Shapiro, page 1C, Baltimore Sun, October 9, 2006. Includes a profile of Scott Rykiel.

- “Devoted to ‘creating wonderful outdoor spaces’”, by Lorraine Mirabella, page 3C, Baltimore Sun, April 1, 2012. An interview with Catherine Mahan on her retirement from Mahan Rykiel, discussing the history of the firm.

- “Unabashed Designers of Delight” [121-minute video] (November 18, 2013). A presentation introducing the design team for the Inner Arbor plan. It includes a presentation by Scott Rykiel beginning at 41:54.

For more on the Chrysalis stage floor see the following:

- Bison Innovative Products and example deck supports and floor tiles.

- Entry for ipe (the hardwood used in the stage floor tiles and pickets) at the online Wood Database.

- Engraving for the Chrysalis stage floor tiles.

For more on the Chrysalis amphitheater and its origins in the Inner Arbor concept plan, see the following:

- Michael McCall presentation of the Inner Arbor concept plan to Leadership Howard County [33-minute video] (September 20, 2013).

- The Chrysalis portion of the Inner Arbor pre-submission community presentation (December 2, 2013).

- Michael McCall presentation to the Howard County Design Advisory Panel [20-minute video] (February 26, 2014).

For more of my opinions on and explanations of various aspects of the Chrysalis and Merriweather Park at Symphony Woods, see the Inner Arbor-related posts in the series “The Inner Arbor plan takes shape” and elsewhere on this blog. (Note that some of these posts contain outdated information relating to park features that were later dropped or revised.)