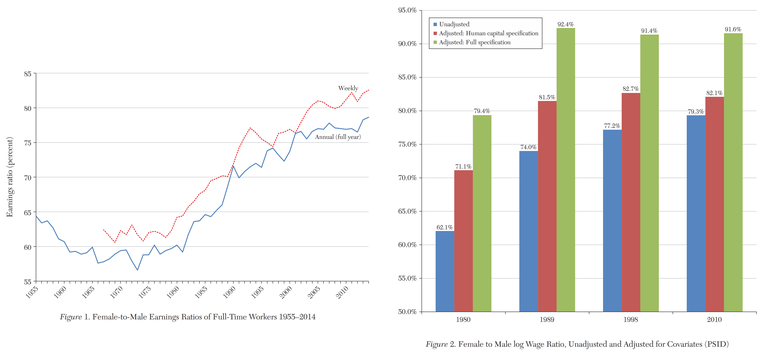

The (unadjusted) gender wage gap in the US over time (L) and the wage gap in selected years after adjusting for various factors (R), including employee “human capital” (including education and experience) and human capital plus additional factors (including industry and occupation). (Click for a higher-resolution version.) Images adapted from “The Gender Wage Gap: Extent, Trends, and Explanations,” Figure 1, page 792, and Figure 2, page 798.

tl;dr: When it comes to gender equality, I don’t think there are any simple solutions, only tentative ways forward.

After a detour reviewing Howard County campaign signs, I’m back to my series outlining my answers to the “Seven Questions” posed by Jason Booms. In this next-to-last post I address Jason’s sixth question:

Considering the UN’s sustainable development goals which refer to gender equality as a “fundamental human right,” how is America performing when it comes to promoting gender equality and what specific steps can and should be taken to secure true gender equality in the United States?

As I did in my post on racial equality, I’ll note up front that questions like this should first and foremost be addressed by people who are most directly affected by the issues under discussion. I’m writing here not because I have any special knowledge of or connection to these issues, but as one voter among many who will be asked to weigh candidates’ positions.

Also, in this post I’m discussing the traditional perspective on gender equality, namely that of women in relation to men. Questions relating to LGBTQIA equality I’ll postpone to the next (and final) post.

This was the hardest post for me to write, because I couldn’t think of one single unifying idea or policy vision around which to organize the discussion. I finally settled on two related topics: the wage gap between men and women, typically thought of as evidence of discrimination and a problem needing correction, and sexual harassment, much in the news recently as a problem impacting the prospects for women’s professional advancement in various fields.

I also consulted only two source documents, both attempting to provide an comprehensive overview of their respective topics, with their own perspectives and potential biases. That means I can’t claim to have a complete picture even of these two topics, so this is at best a starting point for further discussion.

The gender wage gap

When viewed from a high level the story of the gender wage gap is pretty straightforward, as shown in the left graph above: the average woman is paid less than the average man, on both a weekly and annual basis, with women’s income going from roughly two-thirds of men’s income in the 1960s to about four-fifths of their income today. When you see a quote like “women make 78% of what men do” this is the comparison it’s referring to.

However if you look it at this more closely the gap becomes more complicated, and skeptics have the opportunity to raise a host of questions about the causes of the gap, and the extent to which women are actually discriminated against. Labor economists Francine Blau and Lawrence Kahn have written extensively on this topic over the years; the figures above are taken from one of their recent papers. My take after reading their paper is that the raw 22% per cent gap isn’t all due to discrimination, but that the various other factors skeptics have suggested don’t totally explain the existence and persistence of the gap.

The right graph above represents Blau’s and Kuhn’s attempt to explain the gap using the most comprehensive data available to them. They start with the unadjusted gaps as measured in various years from 1980 to the present. Then they attempt to account for “human capital” effects: for example, do men and women receive equal pay if they have the same level of education, the same amount of work experience, and so on. Once this is accounted for the gap narrows by a few percentage points.

Blau and Kuhn then attempt to account for additional factors in their “full specification,” in particular whether men and women receive equal pay if they work in the same industries and occupations. After accounting for these the gap is reduced further, but still exists–and in fact has remained relatively the same for the past 10-20 years.

The datasets they’re using aren’t detailed enough to look into all posible explanations of the gender wage gap, but they cite other research to try to get a feel for how salient those explanations might be. In particular they look at explanations based on gender differences in psychological factors (for example, that women prefer “working with people” to “working with things”) and conclude that “this source of the gender gap, based at least on what we know at this point, while worth pursuing, does not appear to provide a silver bullet in our understanding of gender differences in labor-market outcomes.”

Some other interesting take-aways from this paper:

- It’s possible that one major factor in reducing the gender wage gap was the decline of unions in the manufacturing sector. In other words, things didn’t get better from a gender equality perspective because women got paid more, but because (many) men got paid less.

- “Women [now] exceed men in educational attainment and have greatly reduced the gender experience gap.” In other words, traditional “human capital” explanations for the gender wage gap are now less relevant.

- In recent years the gender wage gap has been “larger for the highly skilled than for others, suggesting that developments in the labor market for executives and highly skilled workers especially favored men.” Although the authors do not draw this conclusion, it’s possible that this persistence of the gender wage gap for more skilled workers helps explain why the issue continues to be so politically relevant: it affects exactly those women who are most likely to be politically active.

- Finally, the authors point out that “recent research suggests an especially important role for work force interruptions and shorter hours in explaining gender wage gaps in high-skilled occupations than for the workforce as a whole.” Depending on one’s perspective we could see this as another example of the power of societal expectations (women being expected to downplay work in favor of family responsibilities) or as an aspect of personal preferences—or perhaps both factors operating simultaneously.

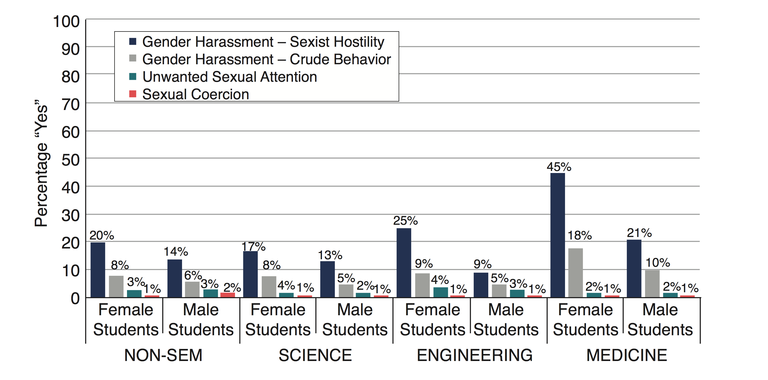

Incidences of harassment of students by faculty or staff at 13 academic institutions in the University of Texas system. (Click for a higher-resolution version.) Image from Sexual Harassment of Women: Climate, Culture, and Consequences in Academic Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Figure 3-3, page 60, original data from the Cultivating Learning and Safe Environments (CLASE) survey.

Sexual harassment

Why might women be less represented in certain professions, might be less able to reach the highest (and best-paying) levels of a profession, or might leave a profession earlier than they otherwise might (thus limiting their lifetime earnings)? One possibility is that certain industries, professions, and organizations make women unwelcome, so that they are less likely to enter them and more likely to leave them.

Sexual harassment in particular industries, professions, and organizations is one thing that might be relevant to this. Certainly recent years have seen a number of high-profile cases of harassment and abuse, highlighted by the #MeToo movement. However that doesn’t directly address how prevalent sexual harassment might be in general.

One source of data on this question is a large survey (over 28,000 students) carried out by the University of Texas System. This survey was in turn one of the major inputs to a National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine report on sexual harassment in STEM fields, along with a similar survey at Penn State. Since these surveys were done at universities their findings aren’t directly applicable to workplaces in general. However they are at least suggestive of what post-university workplaces might be like, especially when looking at the experiences of graduate students (who can be considered entry-level academic employees).

The University of Texas survey found a relatively low incidence of the most severe forms of sexual harassment of student women by faculty or staff: about 1% of student women across all academic disciplines had experienced sexual coercion (“when favorable professional or educational treatment is conditioned on sexual activity”) and about 2-4% across those same disciplines experienced unwanted sexual attention (“verbal or physical unwelcome sexual advances, which can include assault”).

These figures for harassment of students by faculty or staff were about the same for student men, indicating that sexual harassment in its most severe forms is not necessarily something suffered only by women. However, there was a significant difference in the rate at which student women suffered gender harassment, defined as “verbal and nonverbal behaviors that convey hostility, objectication, exclusion, or second-class status about members of one gender.” About a quarter to a half of student women across academic disciplines had experienced these sorts of misogynistic attitudes from faculy or staff, a rate about a third to more than twice as high (depending on discipline) as that for student men experiencing misandristic attitudes.

As alluded to above, student women in some academic disciplines experienced gender harassment at significantly higher rates than in other disciplines: almost half of all student women in medicine experienced this, and about a quarter in engineering. High rates of gender harassment of medical students were experienced by men as well (about a fifth of student men).

The figures from the Penn State survey are not directly comparable, since they’re not broken out by discipline. However in general they echo the findings of the UT survey: a relatively low rate of the most severe forms of sexual harassment, with women and men experiencing this type of harassment at roughly comparable rates, and a relectively high rate of gender harassment, with women experiencing this at a rate significantly higher than men.

So what should we make of all this? I have several thoughts:

First, although this isn’t directly demonstrated by the data in this case, my bet is that sexual harassment in its most severe forms is an outgrowth of a more general atmosphere of gender harassment: just as (for example) lax attitudes towards corruption create an environment in which people predisposed to financial wrongdoing are emboldened to pursue it on a massive scale, I suspect an environment of pervasive gender harassment provides cover for a relatively few people to engage in severe sexual harassment.

Second, although again this isn’t directly demonstrated by this data, sexual harassment (in all its forms) that particularly affects employment prospects seems to be a function of power differentials within the industry, profession, and organization. Thus, for example, the medicical field has long put doctors on a pedestal, and tolerated a sort of professional hazing in the treatment of residents. It’s therefore not surprising that gender harassment of medical students should be particularly widespread.

In general powerful people can get away with harassment and abuse of all kinds: they are seen as indispensable and/or untouchable, and they have equally powerful friends and associates willing to cover for them and protect them from any consequences for their behavior. Sexual harassment is no exception. This scenario plays out in fields from politics and business to science and the humanities, as witnessed by the recent coverage of high-profile sexual harassers in each of these fields.

So, what if anything can be done about this, above and beyond more strictly enforcing legal sanctions already in place? Gender harassment in an industry, profession, and organization is an example of general incivility in professional contexts, and I think can be at least partly addressed in the same way, namely by social promotion and enforcement of norms of professional civility.

The #MeToo movement is in a way an example of this. So too are the first three recommendations of the NAS study on sexual harassment: “Create diverse, inclusive, and respectful environments“, “Address the most common form of sexual harassment: gender harassment,” and “Move beyond legal compliance to address culture and climate.”

However professional norms are greatly influenced by those at the top, who can model good behavior or exhibit bad behavior. Thus in addition to grass roots promotion and enforcement of desired norms, it’s also important to ensure that powerful people can be held to account, and known abusers prevented from exploiting their power base. The #MeToo movement is part of this also, but there are also other potential ways to address this.

For example, one common pattern seen in the sciences is for a “superstar” laboratory head (Principal Investigator, to use the correct term) to engage in multiple incidents of sexual harassment and abuse over the years without any consequences. Among other things, their ability to bring in a continued stream of government grants and other funding makes them valuable to their host universities, and thus causes those universities to dismiss or downplay reports of abuse of students–students who themselves are dependent on the abuser to provide them recommendations for future positions.

Even if universities themselves prove to be uncooperative in disciplining their faculty (which is likely to be the case as long as they value the money and fame superstar faculty members bring), governments can exercise their power over grants. Beyond just denying grants to known abusers (which will be ineffective if abusers are not reported), they can help moderate the “superstar” system by spreading grants to more institutions and making grants less dependent on institutional and researcher reputation, for example by using lotteries or apportioning more grants to young researchers.

(The NAS report on sexual harassment made one recommendation along these lines–“Diffuse the hierarchical and dependent relationship between trainees and faculty,” for example by channeling funding through academic departments rather than through individual researchers–but does not address the overall system of government grantmaking.)

Whether there are similar mechanisms that could work in other fields is an open question. (For example, it’s not clear what could reduce the power of abusive gatekeepers in film or TV.) However I can’t conclude this post without making one final point:

The media have focused on high-profile cases of sexual harassment, including those involving prominent celebrities, and the discussion of obstacles to women’s professional advancement has focused on high-skill professions. However, the brunt of gender harassment and more severe forms of sexual harassment is likely borne by those closer to the bottom of the income pyramid, women stuck in relatively low-paying jobs that they feel unable to leave for various reasons.

I’ve written previously about social insurance proposals to provide universal health care, a basic income, and other means by which people can have increased opportunity and less chance of falling through the cracks of a dynamic capitalist economy. To the extent such measures increase labor mobility and lead women to take more chances in their work lives, I think they may also help address the problem of sexual harassment in the workplace, and perhaps the gender wage gap as well. Rather than being able to exploit a captive and compliant workforce, firms that foster a culture of incivility and harassment may find themselves facing the market discipline of women workers who feel more free to say “no.”

Further exploration

As noted above, for this post I read deeply rather than widely, focusing on two lengthy works that themselves cover a great deal of relevant topics and research.

- Blau, Francine D., and Lawrence M. Kahn. 2017. “The Gender Wage Gap: Extent, Trends, and Explanations.” Journal of Economic Literature, 55 (3): 789-865. DOI: 10.1257/jel.20160995. Reviews research on various explanations for the gender wage gap in the US. (Blau and Kahn have a long history of publications on this topic; this is the most recent one.) See section 7, “Conclusion,” on pages 852-855 for an overall summary.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2018. Sexual Harassment of Women: Climate, Culture, and Consequences in Academic Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/24994. A 312-page report that explores the research on sexual harassment of women in various STEM fields and makes various recommendations for institutional and policy changes. For a condensed version of its findings and recommendations see the 12-page summary.

Other works of interest include the following:

- Cultivating Learning and Safe Environments (CLASE) study. A survey undertaken by the University of Texas System, covering over 28 thousand students at 13 academic institutions within the UT System.

- Sexual Misconduct Climate Survey. A survey undertaken by the Pennsylvania State University system, covering about 11 thousand students. Unfortunately there does not appear to be a single summary report for all campuses, but University Park is the largest campus and its report is presumably representative.

- “Here’s How Geoff Marcy’s Sexual Harassment Went On For Decades,” by Azeen Ghorayshi. A Buzzfeed article discussing how a “superstar” university researcher managed for many years to evade consequences for his sexual harassment of students.