Maryland Governor Larry Hogan speaks at the Niskanen Center conference “Starting Over: The Center-Right After Trump,” December 11, 2018. (Click for a higher-resolution version.) Image posted to Governor Hogan’s official Twitter feed, photographer and copyright status unknown.

tl;dr: The Niskanen Center promotes a pro-market pro-government vision for the center-right, but I think the sales pitch needs to be tweaked to get at least some conservative voters to buy it.

What’s my beef with the Niskanen Center?

I know the Niskanen Center (having read its blog for the past few years). I like many of the Niskanen Center’s policy recommendations (see my “seven answers” series). I even donate to the Niskanen Center. So why I am writing this long blog post (gently) chastising the Niskanen Center? For the answer read on (but feel free to skip over the next section or two if you already know the material).

The Niskansen Center advertises itself as “a moderate, nonpartisan think tank that works to promote an open society and change public policy through direct engagement in the policymaking process.” In other words, it’s engaged in the political equivalent of what we in the IT business call “enterprise sales”: trying to get high-level decision makers to buy what you’re selling and implement it in their organizations.

Recently the Niskanen Center has stepped up its sales efforts, releasing a white paper laying out a comprehensive vision “that sees government and market as complements rather than antagonists” and proposes a “new synthesis [to] help move our divided society toward the best version of itself and away from the toxic tribalism that afflicts us today.” The Center also sponsored a one-day conference “Starting Over: The Center-Right After Trump” featuring various conservative and libertarian thinkers, with a special guest appearance by our own Governor Larry Hogan.

Is the Niskanen Center pursuing an effective sales strategy? If not, how could it be improved? And why as a lifelong Democrat would I be interested in their success, especially if the result is to improve the future electoral fortunes of the Republican Party?

This is apparently the first cartoon showing the Republican elephant and Democratic donkey in opposition to one another. As a reminder that the two parties were not always as they are now, the Republican elephant represents the Union and the Democratic donkey the Confederacy; “Jeff” is lifelong Democrat Jefferson Davis. (Click for a higher-resolution version.) Public domain image originally published by E. B. & E. C. Kellogg and George Whiting in 1861 or 1862, made available by the American Antiquarian Society.

Why be a moderate in a two-party system?

It’s clear that the Niskanen Center sensibility has no natural home in a two-party system driven by winner-take-all elections and prone to polarization. In the US the only strategy open to the Center is to attempt to have its preferred policies adopted by either the Democratic or Republican Party.

As it happens many of those policies, including proposals for universal health care and other forms of social insurance, are more compatible with the positions of Democratic elected officials and their voters. So why is the Niskanen Center trying to cultivate support from Republicans and promoting a hoped-for moderate makeover of the Republican Party?

Leaving aside the past “fusionism” that saw libertarians ally with conservatives, a more plausible reason for its outreach to Republicans is simple electoral math: The structure of the US Senate and Republican domination of small rural states makes it very likely that Republicans will maintain control of the Senate for the foreseeable future, or will at least be able to block Democratic legislation if they vote as a unified bloc.

Advancing the Niskanen Center’s preferred policies (many of which are my preferred policies) will thus require gaining the support of at least some Republican legislators willing to go against conservative orthodoxy. Hence it’s joining with others in the quest to revive that almost-extinct species, the “moderate Republican” (and hence my interest as a Democrat in that quest).

Romans fighting barbarians (perhaps the same barbarians whose descendants created western European civilization). (Click for a higher-resolution version.) Public domain image from Old England: A Pictorial Museum by Charles Knight, made available by fromoldbooks.org.

Civilization vs. the barbarians

But how likely is it that moderate Republicanism can be revived? Larry Hogan won re-election by a substantial margin, and is now being feted by some Republicans looking for an alternative candidate in 2020. However I suspect that Hogan would not make it out of a Republican presidential primary anywhere in the US, including Maryland.

On the flip side, in the affluent, educated, suburban/exurban jurisdiction of Howard County, Maryland (traditionally a swing district), self-proclaimed “independent leader” and Hogan ally Allan Kittleman saw his own brand of moderate Republicanism go down to defeat at the hands of progressive African American Democrat Calvin Ball.

Hogan’s problem will likely be that he won’t be perceived as conservative enough by most Republican voters. Kittleman’s problem was possibly that when he attempted to adopt a more conservative position, as in his opposition to so-called “sanctuary” legislation for Howard County, it turned off some Democratic voters who might otherwise have been inclined to give him a second term.

I think the Niskanen Center, and those Republican candidates influenced by it, will have a similar problem. To diagnose it further I’ll enlist the help of Arnold Kling’s model of the three axes (or languages) of politics:

Due to its libertarian background the Niskanen Center has no problem speaking the language of libertarians where appropriate. Per Kling the preferred libertarian framing is that of the state vs. those subject to state coercion. The Niskanen Center’s promotion of the free market and support for reducing excessive government regulation plays right into that framing.

The Niskanen Center policy vision also at times echoes the preferred framing of progressives (per Kling), of the oppressed seeking to escape oppression and overthrow their oppressors. For example, the paper argues that “regardless of the justice of our contemporary rules, people’s capacities, social standing, and social capital are inheritances of previous rules that may have been profoundly unjust.”

However it’s hard to find in the Niskanen Center policy vision the framing that Kling claims is preferred by conservatives, namely that of a civilization under assault by barbarians and defending itself against them. This is especially true when we consider culture with a capital “C,” as in “Western Culture” or “American Culture.” (The word “culture” nowhere appears in the Niskanen policy vision paper.)

The Republican Party seems to have committed itself to a particular ethno-nationalist version of the “civilization vs. barbarians” framing, one that has resonated with many of its voters, portraying a white Christian civilization under attack by those who are non-white and/or non-Christian. This framing drives the political positions and electoral strategies of a host of Republican candidates, from local offices to the highest office in the land, particularly when it comes to immigration—the very issue driving the partial shutdown of the US government as I write.

This framing harks back (in one form or another) to Reconstruction and the antebellum nativist movement. The Niskanen Center, along with like-minded others, implicitly dismisses it as a nativist fantasy and attempts to counter it through cold hard facts, as in its “Guide to Answering Ten Commonly Asked Questions on Immigration.” But the ethno-nationalist version of the “civilization vs. the barbarians” framing is resistant to such an approach, relying as it does on a way of looking at the world that is congenial to conservatives and thus easily exploited by conservative candidates seeking electoral office.

I think the better approach is not to dismiss the “civilization vs. the barbarians” framing out of hand. Rather I’ll try to interrogate it more closely, to see if a different version of the “civilization vs. the barbarians” framing could be created to make the Niskanen Center vision more congenial to conservatives. In this I’m motivated by the words of the vision paper itself, that “we have an obligation to try to justify our beliefs in terms [our fellow citizens] can recognize.”

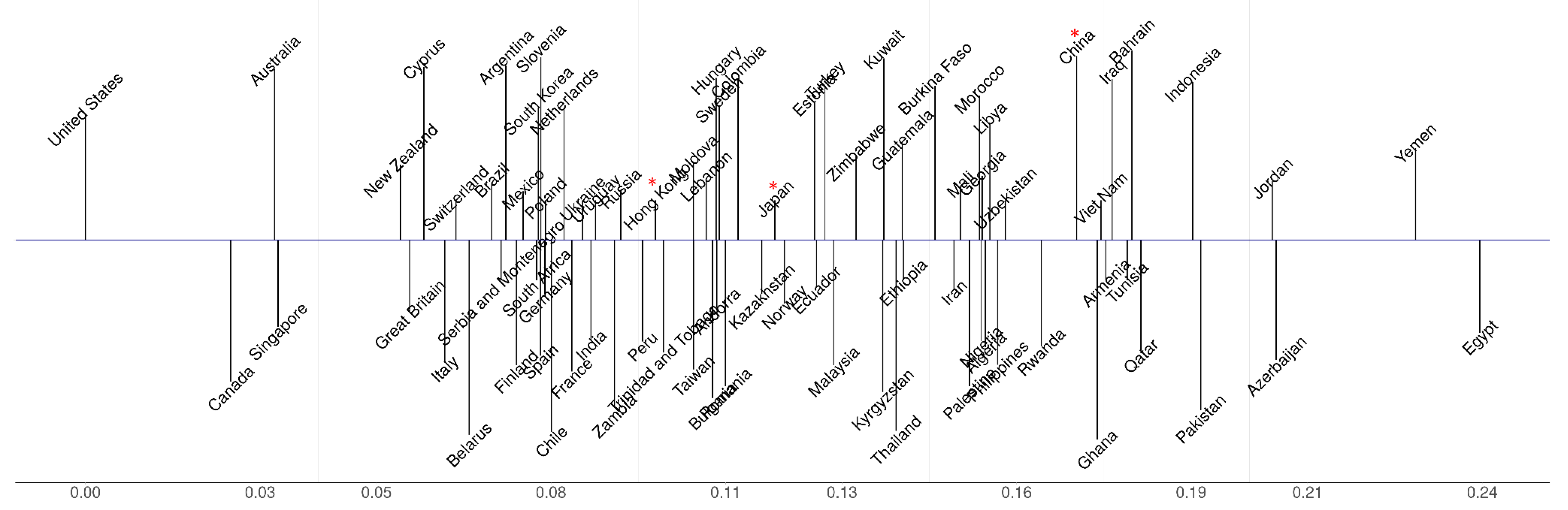

A graph showing the cultural distance (CF ST ) from the United States to selected countries, as calculated using responses to the World Values Survey. (Click for a higher-resolution version.) Image adapted from Figure 9 of “Beyond WEIRD Psychology: Measuring and Mapping Scales of Cultural and Psychological Distance” (pages 39-40).

Cultural distance and American exceptionalism

In exploring the question of reinterpreting the Niskanen Center vision in a conservative framing, let’s start with the concept of “American culture”: a set of “socially communicated practices and beliefs” (to use Arnold Kling’s definition) characteristic of Americans. American culture is typically portrayed by conservatives as being derived from (white) European Christendom, and conservative political rhetoric often implies that it is not or cannot be shared by the non-white or non-Christian.

As is often the case, reality is more complicated, at least according to researchers studying cultural evolution and attempting to formulate better measures of cultural and psychological “distance” between countries. The construction of such measures is quite technical, but the basic concept is relatively simple to understand:

Consider a representative sample of Americans answering questions about their various beliefs: “How important is family to you?” “How often do you attend church?” “How much do you trust strangers?” and so on. For a given question the surveyed Americans will likely vary in their answers, but there will be a “typical” answer and some variation around the typical answer.1

Now consider the same question asked of people in another country. Again this will produce a typical answer and variation in the answers. Finally, combine their answers to the question with those of Americans, looking at the typical answer and variation in the answers of the two countries’ respondents considered as a single group.

In some cases, as with American and Canadian respondents, the typical answer and variation in answers in the combined sample may differ very little from the typical answer and variation in answers produced by the American respondents alone. With another country (call it “X”) there might be significant differences in the combined answers and the American-only answers: country X’s respondents may have a different typical answer to the question, and/or their answers to the question may vary more or less than those of the American respondents.

These smaller or larger differences can then be used to calculate a measure of “cultural distance” between the US and another country relative to that particular question.2 This cultural distance value will be close to zero for a country like Canada in our example, but larger for our example country X.

Now consider not a single question but a survey consisting of many questions, covering an entire range of attitudes and beliefs. The answers to this set of questions can be used to calculate a single value of cultural distance between the US and another country, which the researchers refer to as CF ST .3

The graph above shows the cultural distances (CF ST values) from the United States to each of a selected group of other countries, as calculated using answers to the questions on the World Values Survey.4 The cultural distance from the US to a given country can be roughly interpreted as the percentage of variation between the US and that country relative to the total variation within the two countries considered together.

Some of the results of those calculations accord with the ethno-nationalist version of the “civilization vs. the barbarians” framing: Canada is the closest country to the US by this measure, followed by other countries in the Anglosphere, while the countries furthest in cultural distance from the US are those with Muslim majorities. Other results are less consistent with this framing: for example, by this measure Brazil, Argentina, and Mexico are closer culturally to the US than European countries like France, Germany, and the Netherlands.

(Ethno-nationalists might interpret this as evidence of the effect of Hispanic migration to the US. However this seems contradicted by the small cultural distance between the US and Canada, which has a very small Hispanic population—on the order of 1-2%. Alternately they might claim that extensive Muslim immigration is driving European countries further away in cultural distance from the US. Again this seems implausible, as Great Britain, a country with a Muslim population percentage as high as Germany and almost as high as France or the Netherlands, is at almost the same cultural distance from the US as New Zealand, a country with a very small Muslim population—again on the order of 1-2%.)

Another point is that even for countries maximally culturally distant from the US, variation between those countries and the US is a relatively small fraction (less than a quarter in the most extreme case) of the variation within the countries considered together. The typical resident in such countries will have attitudes and beliefs significantly different than those of a typical American, but even in such culturally distant countries there’s likely to be a significant number of people whose attitudes and beliefs are consistent with those of mainstream American culture.

I’ll revisit this point below, but I first want to consider a different question: Why is American culture (and by extension Anglosphere and European culture) relatively exceptional relative to the cultures of other countries, and what implications does that have for the “civilization vs. the barbarians” conservative framing?

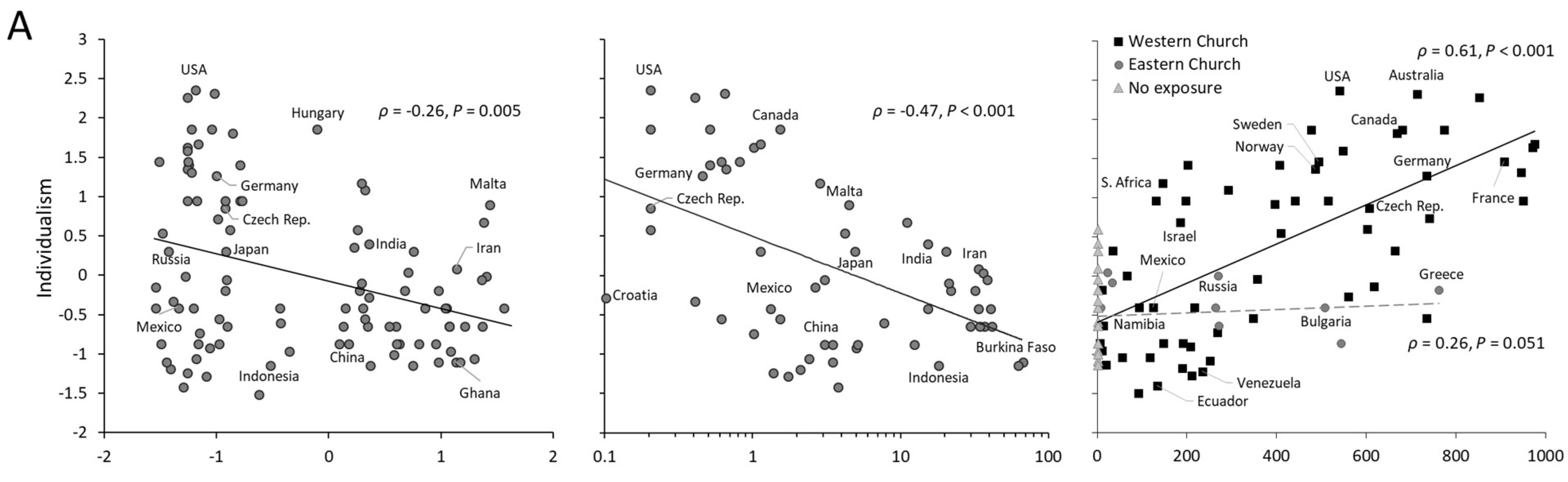

Three graphs showing the correlation of individualism in various countries with an index of kinship intensity, the prevalence of cousin marriage, and exposure to the Western (Catholic) and Eastern (Orthodox) churches respectively. (Click for a higher-resolution version.) Image adapted from Figure 3 of “The Origins of WEIRD Psychology” (page 11).

How the Church created liberal democracy

Part of the ethno-nationalist version of the “civilization vs. the barbarians” framing promoted by many conservative politicians is that American culture, and Western culture in general, is inextricably linked to European ancestry and the Christian religion. In contrast, the same researchers responsible for the measure of culture distance discussed above also argue that Western culture and its associated psychology are simply due to an odd accident of history.

Their hypothesis, supported by considerable evidence, is that the typical psychology of those living in Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic (WEIRD) countries has its ultimate roots in the decisions of the leaders of the Catholic Church in late antiquity to enact strict prohibitions on marriage between couples related even to the slightest degree.

These prohibitions had the affect of breaking up traditional social arrangements based on kinship within extended families. The resulting changes in culture favored those people who had a more individualist outlook, who owed less to their extended families and more to the efforts of themselves and their immediate families, and who were able to cooperate with unrelated others for their mutual benefit.

The three graphs above represent a small part of this argument. The first graph shows that present-day individualism in various countries (as measured by the Hofstede scale) tends to be less in countries with a previously high intensity of kin-based institutions (as measured by the Kinship Intensity Index). The second graph shows that the same lessening of individualism is present in countries with a higher prevalence of marriage between cousins. Finally, the third graph shows that individualism tends to be higher in countries that have had more centuries of exposure to the Western (Catholic) church.

If true this hypothesis has some interesting implications. In particular it implies that what are thought to be unique characteristics of Western culture—greater individualism, creativity, trust in strangers, impersonal cooperation and altruism, and lessened obedience, conformity, and traditionalism—have little or nothing to do with actual Christian beliefs. (Among other things this is implied by the experiences of countries like Russia that have been primarily exposed to the Eastern church, the theology of which does not differ significantly from that of the Western church.)

This also implies that there is no inherent reason why countries with non-Christian and/or non-white majorities that are currently more culturally distant from the US could not have developed—or might yet develop—cultures more similar to those of the US and other Western countries, if kinship arrangements in those countries had been (or are in future) similarly altered to emphasize nuclear families as opposed to extended ones.

The Battle of the North Inch (also known as the Battle of the Clans) in Perth, Scotland, in 1396 (L); and the Santa Claus parade in Vancouver, Canada, in 2017 (R). (Click for a higher-resolution version.) Painting in the collection of the Perth Museum and Art Gallery, presumed to be in the public domain. Photograph © 2017 by GoToVan, used under the provisions of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0) license.

Rethinking the civilization/barbarian axis

What are the implications of the research discussed above for the “civilization vs. the barbarians” conservative framing? Who in this conception are the real barbarians, and what is the civilization that conservatives—and everyone else—should be called upon to defend?

Here I rely on the thesis put forth by Mark Weiner: that the only alternative to the modern liberal state is “a form of governance that unites a radically decentralized constitutional structure with a culture of group honor and shame . . . and makes the extended family the constitutive unit of society, politics, and law.” In other words, the rule of the clan.

By breaking the bonds of kinship formed by intermarriage within an extended family, the Catholic Church arguably created the preconditions for the emergence of a liberal order that valorized individual autonomy, had some concept of the public interest (as distinct from clan interests), and based governance on a set of impersonal institutions that (at least in theory) existed for the benefit of everyone equally. In other words, the rule of law.

We can see what the rule of the clan looks like by looking at other countries around the world, especially those culturally distant from the US. We can also look into the past, at the European societies that emerged from the rule of the clan. The painting above shows one example: a staged battle in which men from two Scottish clans butchered one another over some matter or other touching on their clans’ honor.

According to Weiner, as the rule of the clan recedes the bonds of extended kinship lose their power over the individual but live on in benign form as part of individuals’ cultural heritages, one way in which they situate themselves within society and in the story of humanity. As shown in the photograph above, a group of Scots marching together is no longer a sight to be feared by their clan’s enemies, but simply an occasion for people to express pride in their heritage.

The barbarism we should combat is thus not clannishness as family feeling but anti-social clannishness, that prioritizes clan over country and the interests of one’s fellow Americans. (By “anti-social” I of course mean this in American terms. In a clan-based society it would be anti-social not to put your own clan’s interests above others.)

This anti-social clannishness comes in many forms: the criminal gangs bound by ties of family and ethnicity; the terrorists who kill and maim others in the name of ethnic and religious solidarity; the parents who kill their children for perceived violations of family honor; the businesspeople who think nothing of cheating and defrauding those of different ethnic groups or religions; and (last but not least) the demagogues who promise to support “the people” but instead use their political positions to enrich themselves and their families.

In this framing the civilization that we seek to protect from barbarism is that of the rule of law, of individual autonomy, of “free minds and free markets,” of peaceful toleration of those with whom we disagree, and of a public interest broadly defined to encompass the needs and desires of all Americans, no matter their heritage or station in life.

How might this alternative framing, what I’ll call “rule of law conservatism” or “anti-clan conservatism,” play out in term of policy? In particular, can we talk about immigration policy in a way that is consistent with both the Niskanen Center vision and with this different framing?

The Statue of Liberty seen at sunset behind the main building at Ellis Island. (Click for a higher-resolution version.) Image © 2011 by Peter Miller, used under the provisions of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) license.

The immigrants we want

Those who lobby for immigration restrictions characterize their opponents as advocating for “open borders.” Immigration supporters object to this, and rightly so, because very few people argue for no restrictions on immigration at all.

However I think the “open borders” charge is politically effective because it captures a common feeling: that beyond a few limited cases (like denying entry to criminals and suspected terrorists) immigration supporters are perceived as being unwilling to make judgements, particularly moral judgements, about which immigrants we want to attract to the US and which we don’t.

The ethno-nationalist version of the “civilization vs. the barbarians” framing offers a simple and politically potent response to this, designating some countries as unacceptable sources for immigrants based on their being non-white and/or non-Christian.

The alternative “rule of law vs. anti-social clannishness” framing, combined with the research I’ve cited, may offer a alternative approach: Given the amount of variety in cultural attitudes within each country, even in those countries culturally distant from the US, there are likely to be many people around the world whose attitudes, beliefs, and personalities are “American-like,” and who would therefore make good US citizens.

In fact, it may even be in the more culturally distant countries where we might find the best candidates for US citizenship. Any “American-like” people in those countries will likely feel all the more strongly the cultural gap between themselves and their countries’ dominant cultures, and will likely be the most motivated to assimilate to American culture as immigrants. In other words, they will be the people most “yearning to breathe free.”

We also can infer from the cited research that being non-white or non-Christian is not in and of itself an inherent obstacle to being a good American. What really matters is that prospective immigrants not be predisposed to anti-social clannishness that violates American norms and is inconsistent with American culture.

So how would this alternative framing cause us to rethink US immigration policy? Or would it necessarily?

For example, the Niskanen Center has defended the lottery-based “diversity visa” program, partly on the basis that in practice those admitted under the program do better than other immigrants. It’s likely that those who are most attracted to the American way of life, and most predisposed to be compatible with it, are going to be the most motivated to jump through the many hoops that entrance under that program requires.

In another example, US family-based immigration policy already prioritizes uniting of nuclear families over uniting extended families. It’s not immediately clear to me how it could be tweaked to further discourage immigration by those predisposed to anti-social clannish behavior.

It’s possible that what is needed with US immigration policy is not a major overhaul (although there may be useful reforms that could be made). It may simply be that we need a different way of talking about immigration: that we can and should have clear criteria about who to admit to the US as immigrants and who not to admit, but that such criteria should consistent with a “rule of law vs. anti-social clannishness” framing as opposed to an ethno-nationalist framing.

This also implies that we should not be shy about valuing and promoting a common American culture and identity based on freedom, individualism, and the liberal order. This culture and identity can and should ultimately take priority over the many ethnic, religious, and other cultures and identities to which individual Americans belong.

As the Niskanen Center vision paper notes, “the liberal democratic capitalist welfare state [is] the best model of governance ever devised, producing the richest, healthiest, best-educated societies that ever existed.” But I think the Niskanen Center needs to go further and recognize that the liberal democratic capitalist welfare state exists only because Americans, and others like us, have a particular culture that makes it possible for such a state to emerge and flourish, and that the continued existence of that state is dependent on our willingness to promote and defend that culture.

This I think is the missing piece in the Niskanen Center vision, one that may help it justify its policy program to conservatives, just as the Center has acknowledged the concerns of libertarians and progressives and tried to justify its vision to them in terms they can recognize.

It’s possible, if not likely, that this reframing of the “civilization vs. the barbarians” axis will not attract the support of most conservative politicians and voters, that they will still be wedded to a framing based on ethno-nationalism.

But if even a few conservative politicians can win electoral success campaigning on an alternative vision of America, that may be enough to implement the Niskanen Center’s preferred policies in alliance with those from the other side of the aisle. The Niskanen Center seems to be playing a long game, and in that game even the smallest of advantages may be the key to ultimate victory.

For further exploration

For more on the Niskanen Center and its policy vision, see the following:

- Niskanen Center Conspectus lays out in more detail the goals and strategy of the Center, based on its theory of policy change as “a product of intense insider activity to overcome profound status quo biases in the political system—biases that are not easily moved by external political pressure or material resources.”

- “The Center Can Hold: Public Policy for an Age of Extremes,” by Brink Lindsey, Will Wilkinson, Steve Teles, and Samuel Hammond, attempts to combine the Niskanen Center’s various policy positions into a single coherent vision that “rejects the false dichotomy between ‘big’ and ‘small’ government and combines the best aspects of the ‘pro-market’ right and the ‘pro-government’ left.”

- “Starting Over: The Center-Right After Trump” was a one-day conference exploring “political prospects for a new center-right, and the policy ideas and ideals that can revitalize the post-Trump Republican Party.” Among other things, it featured a welcoming address by Maryland Governor Larry Hogan. Unfortunately there are no transcripts for the conference audio, and no audio for Hogan’s remarks.

- “Is Hogan the antidote to Trumpism?,” by Josh Kurtz for Maryland Matters, and “Maryland’s Hogan speaks to GOP dissenters looking for alternative to Trump,” by Ovetta Wiggins and David Weigel for the Washington Post, report on Hogan’s appearance at the “Starting Over” conference and the part he might play in a potential future Republican Party more receptive to the Niskanen Center’s ideas.

- “A Guide to Answering Ten Commonly Asked Questions on Immigration” and the various policy briefs on immigration provide a comprehensive picture of the Niskanen Center’s views on immigration and related issues.

The following are a representative sampling of reactions to the Niskanen Center policy vision:

- “A new center being born: The market and the welfare state go together” by David Brooks for the New York Times. In one of the most enthusiastic responses to the paper, Brooks writes that he “felt liberated to see the world in fresh new ways, and not only in the ways I’ve always seen them or the way people with my label are supposed to see them.”

- “What would a responsible center-right party do?” by Jennifer Rubin for the Washington Post. Rubin writes that “[The paper’s] greatest contribution might be in its recognition that ‘small government’ is a slogan and a canard, and too much effort in the right is spent (intentionally or not) on policies that inhibit widespread prosperity.”

- “I have seen the future of a Republican party that is no longer insane” by Jonathan Chait for New York magazine. Chait writes that “[The paper] synthesizes two years of heresies into an impressively coherent approach to governing,” with the Niskanen Center “operating from the starting point of what a well-functioning right-of-center party ought to stand for, rather than how the current one can be tweaked.”

- “The Niskanen Center is a splendid policy shop, but it is not the future of the Republican Party,” by Jeet Heer for The New Republic. Heer claims that the Republican party will not find the Center’s vision compatible with its base’s desire for “culture-war theater, white nationalism and tax cuts.”

The following sources provide background for my comments on modifying the Niskanen Center to make it more attractive to conservatives:

- “Culture Matters” by Virginia Postrel for Econlib. Postrel argues that libertarians and classical liberals do not understand culture but need to learn more about how it works and evolves.

- “It is sometimes appropriate . . .” is a blog post by Arnold Kling in which he (to my knowledge) first set out his model of political discourse, including conservatives’ use of the “civilization/barbarian” axis. Kling later expanded his thoughts into a book, The Three Languages of Politics.

- “Beyond WEIRD Psychology: Measuring and Mapping Scales of Cultural and Psychological Distance” by Michael Muthukrishna, et.al., is a preprint of a paper outlining an approach to measuring cultural distance between countries based on their inhabitants’ responses to the World Values Survey. See also the web site culturaldistance.com for supplemental material.

- “The Origins of WEIRD Psychology by Jonathan Schulz, et.al., argues that the “peculiarity of populations that are Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich and Democratic (WEIRD)” in part “arose historically from the Catholic Church’s marriage and family policies, which contributed to the dissolution of Europe’s traditional kin-based institutions.”

- “The Catholic Church, Kin Networks and Institutional Development” by Jonathan Schulz. In this “job market paper” building on “The Origins of WEIRD Psychology,” Schulz extends the argument that the “Catholic Church’s medieval marriage policies dissolved extended kin networks and thereby fostered inclusive institutions.”

- The Rule of the Clan: What an Ancient Form of Social Organization Reveals About the Future of Individual Freedom by Mark Weiner discusses governmental institutions in societies dominated by kinship-based clans, and how such societies can evolve to become liberal societies based on individualism and the rule of law. Weiner summarizes his argument and applies it to geopolitics in his article “The Call of the Clan” for Foreign Policy.

More correctly, the “typical” answer is the mean of the answer values (e.g., “agree,” “strongly agree,” etc., converted to numeric values) and the variation is the variance of the answer values. ↩︎

Specifically, the cultural distance for a single question is the variance of the mean answers for each of the two countries relative to the mean answer for the two countries considered together, divided by the variance of all answers for the two countries considered together. ↩︎

The expression CF ST is used by analogy to the similarly calculated measure F ST used in estimating the genetic distance between two biological populations. C is for culture, F is for “fixation index” (the term used in population genetics, for reasons too complicated to explain here), and S and T represent subpopulation (e.g., an individual country’s respondents) and total population (e.g., the combined set of respondents) respectively. ↩︎

It’s important to remember that a particular value for cultural distance is relative to the survey whose responses were used to calculate it. Using another survey with different questions, or using only a subset of the questions on the original survey, might produce a different value for cultural distance. ↩︎