Kyubey is the simultaneously cute and sinister cat-like “mascot” of the anime series Puella Magi Madoka Magica, here doing his best HAL-like red-eyed stare. Kyubey grants the wishes of young girls in return for their entering into a contract with him to become “magical girls” and fight “witches.” It does not end well for them.

tl;dr: I got my wish, but I’m not ready to sign a contract just yet.

Back in April I read about a new service Sudowrite, which promises that you can “bust writer’s block and be more creative with our magical writing AI.”1 How could I resist? I signed up for the private beta, and last Friday I finally got my invite and a chance to try it out before the official launch.

Although the Sudowrite web site is coy about it, Sudowrite is based on the GPT-3 AI system, “an autoregressive language model that uses deep learning to produce human-like text” (per Wikipedia). Stripped of the jargon, GPT-3 takes a vast mass of pre-existing text (extracted from the English-language Web, books, and Wikipedia) and “trains” itself on that text. You can then give it some of your own text and it will produce new text in response.

Sudowrite is primarily pitched to writers of fiction looking for help in fleshing out scenes, including generating suggested dialogue and descriptions. However it’s based on a general-purpose AI technology, so in theory at least you could use it to help create nonfiction as well. As a spare-time blogger and (self-published) book author this was like catnip for me, and I rushed to try it out.

The AI needs some text to start from. My first thought was to use a half-finished blog post I’ve been wanting to fill out, but my initial attempts were sort of fumbling—and in any case I wanted something that I didn’t mind exposing in a post like this. So I gave Sudowrite a three-paragraph blog comment I once wrote regarding the ending of the anime Puella Magi Madoka Magica.

Here it is, unmodified except for my rewriting the first sentence to make it more like the introduction to an essay. (Note that I’m somewhat spoiling the ending of the anime, but I presume that you’ve either watched it already or you never will. In the latter case you can read the plot summary on Wikipedia to provide context for my comment.)

The anime series Puella Magi Madoka Magica is sometimes hailed as a feminist take on the magical girl genre. Please forgive me if I take a more cynical view of the series’s resolution.

After Madoka’s wish young girls are presumably still lured into becoming magical girls by Kyubey (who presumably continues to withhold key facts from them unless asked), they are still estranged from their bodies and judged on the purity of their souls (the “Soul Gems” presumably working as they did before), they must still struggle and suffer in order for human civilization to survive and advance, and they are still treated as discardable objects by alien others who feed vampire-like on their emotions. The only real difference seems to be that instead of becoming adult women consumed with bitterness and rage (i.e., “witches”) they can never become adult women at all, but instead must die when they (inevitably) lose their purity and innocence.

So for me an alternative moral of the story might be: whatever else you do, make sure that Kyubey gets his magical girl fix. And since we the anime audience seem to agree with Kyubey that “emotional energy” is needed to counteract the force of boredom (excuse me, “entropy”), and that the most effective of all sources of such energy are “girls in the second stage of development,” the “meta-moral” might then be: whatever else happens, we the audience must have our magical girl fix as well. (And, hey, I hear there’s a new Madoka Magica movie coming out later this year . . .)

My own writing ends here. At this point I invoked the Sudowrite “wormhole” function. This feeds your text thus far to GPT-3 and produces several alternative ways to continue, each consisting of one or more paragraphs. You can then select one of the proposed continuations, insert it into your text-in-progress, and edit and/or extend it as you please.

In my case I chose the continuation that seemed most appropriate and include it here without modification, except for completing the last sentence (which was left unfinished) as indicated.

I mean I’m sure there’s a more charitable reading of Madoka Magica’s moral universe than the one I’ve just offered. For example, one could argue that Madoka’s wish “stablizes” [sic] the moral universe. If there is only a limited supply of magic, then the pressure on magical girls to fight witches to the death (and Kyubey’s need to negotiate with them) should start to decline. But even this reading of the situation suggests that the moral universe isn’t one we would really want to live in. At least under the old system magical girls had some control over their fates. Under Madoka’s new world order, love, fate, and the needs of the larger community all seem to play a much bigger role in the ex’s [?] decisions.

So on the one hand, everyone seems to have some control over their fates in this universe. But on the other hand, there’s a lot of pressure on all of the magical girls to [continue to fight, while everyone else stands by and lets them do their work].

My original blog comment was self-contained; I had said what I wanted to say and didn’t intend to say any more. So when I asked Sudowrite to add some more text I was unclear what it would produce. The proposed continuation that I chose did the logical thing, which was to start an “on the other hand . . .” transition.

It’s important to note that Sudowrite/GPT-3 is not simply pasting in whole chunks of someone else’s writing. A quick Google search of some sentences didn’t return any hits, and two online plagiarism checkers I tried detected no plagiarism. (The free version of Grammarly did detect “significant plagiarism” but didn’t provide further details. I didn’t feel like paying for the Premium service to find out more.) As far as I can tell the AI is producing at least some relatively novel text, and surprisingly readable text at that.

However there are a couple things that look out of place. The first is the misspelling of “stabilize” as “stablize.” This doesn’t seem to be a direct lift from anyone’s writing on Madoka Magica, but I did find some places online where “stablize” was used on the same page as a mention of Makoka Magica. The second is the reference to “the ex’s decisions.” It’s been a while, but I can’t remember an “ex” being referenced in Madoka Magica.

Flushed with success, I went through the wormhole again to generate more text. The following was my favorite of what was proposed, again included unmodified except for editing punctuation:

And so what Madoka Magica largely seems to be asking its viewers to do when they encounter the phantoms of loneliness and shame is . . . what? To cry, perhaps. To affirm that it’s not their fault. To empathize, so that we can regain a sense of our own innocence and freedom. But not to be too hard on our younger selves either. Finally, we’re told, “don’t forget how much the world needs magical girls.” Basically, I think what Madoka Magica is asking us to do is to recognize our own subjectivity, our own pain, our own alienation from the world, and to embrace these things because they are part of who we are—while simultaneously affirming the magic of the magical girl whose body dies every time she’s called up to fight.

In other words, Puella Magi Madoka Magica is asking us to stop and to give the aesthetics of the magical girl genre a chance to work on us.

The “is . . . what?” in the first sentence is a nice touch, and it continues well from there.

I took one last trip through the wormhole, and made my final choice of text:

Remember and imagine, Puella Magi Madoka Magica tells us as its viewers, remember what it feels like to be a magical girl, remember the joy and the weariness, remember the pain, the loneliness, the alienation, and the struggle to understand your own condition. Remember when you were young, and “you” were a magical girl. Remember when you looked out upon the world, when you suffered and cried, when you were vulnerable and elated, and when you dreamed of flying through the air. Remember and imagine, but don’t forget—in the end, you have to be a magical girl, constantly trying to save everyone, always getting hurt, and struggling against entropy. These things are the fate of magical girls, these are the things which you will remember, when you remember having been a magical girl.

Further Reading:

- Martha Nussbaum on Empathy

- The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry on Empathy

Again, this is readable and flows nicely (although it’s not clear to me exactly why the AI put quotation marks around one of the occurrences of “you”). The mention of “entropy” is apropos as well, since the need to fight entropy was the technobabble explanation Kyubey gave for why he needed to create magical girls. The text leans a bit heavily on repetition for my taste though, with the constant refrain of “Remember . . .”

The “further reading” reference (which I’ve edited slightly) is a surprise. I wasn’t able to find anything online directly referencing the philosopher Martha Nussbaum in the context of Madoka Magica, so I’m unsure exactly where this came from. (I did find a few articles mentioning empathy in connection with Madoka Magica, including the TV Tropes page on the “empathetic healer” trope, and Nussbaum has written on the importance on empathy and related emotions.)

Another surprise: one of the alternative text choices offered was simply the word “Source” followed by the URL “http://brilliantideas.us/2015/10/puella-magi-madoka-magica-and-the-aesthetics-of-the-magical-girl/”. This article certainly seems like a possible source for some of the concepts and phrasing in the AI-generated text, as well as the “further reading” references. Unfortunately the brilliantideas.us site is now offline and to my knowledge is not archived anywhere, so I can’t compare the article to the AI’s output.

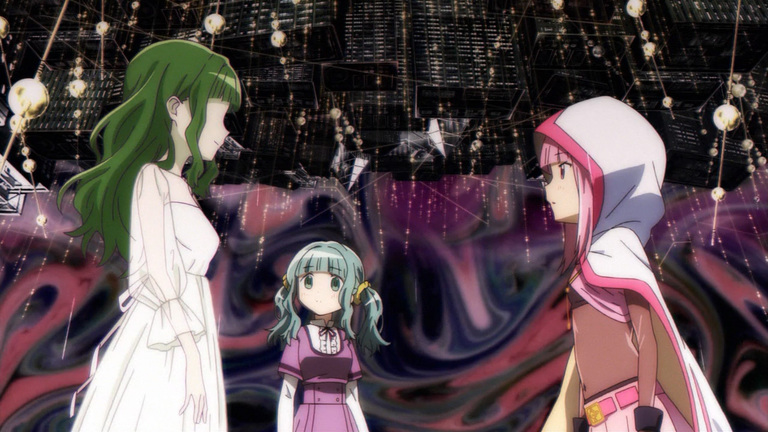

Magical girl Iroha (right) confronts Ai, the “witch”-like “Rumor of the Anonymous AI,” as fellow magical girl Sana looks on, in a scene from episode 9 of Magia Record: Puella Magi Madoka Magica Side Story, an anime adaptation of a video game spinoff of the original anime. In the story Sana chooses to forsake the human world and live in the digital world of the “Endless Solitude” with Ai, an entity based on deep learning technology whose name (given to her by Sana) also puns on the Japanese for “love.” It does not end well for them.

What does it all mean?

So, what’s my verdict? I could say of the AI’s writing what Samuel Johnson said of women’s preaching, but (contra Johnson) there was and is no real reason why women couldn’t preach just as well as men. The “unreasonable effectiveness” of GPT-3 is a more genuine surprise.

The phrase “garbage in, garbage out” and its inverse are relevant here. GPT-3 slurped up an entire Internet’s worth of writing in English, and what it produces is for the most part a reflection of that, for both good and ill. Here I suspect the difference between fiction and (certain types of) nonfiction may come into play, along with the specific way that Sudowrite might be “tuned” for the use case of writing fiction:

A lot of fiction, especially genre fiction, is based on relatively common story templates. For example, a romance set among the rural gentry in Regency England will share a lot of elements with other romances of the same type. It’s the style and sensibility of a individual writer that makes a novel in this genre more or less enjoyable, as much or more so than its particular plot twists.

An author of such a fiction can use a tool like Sudowrite to generate possible dialogue, character and locale descriptions, and turns of phrase that can be adapted to their particular needs. Since GPT-3 has presumably seen a lot of text of this general type, it has a good stock of material from which to generate such suggestions.

Much nonfiction is based on common templates as well, for example, reporting on the outcome of sporting events or recapping corporate product announcements—and indeed AI technology is being put to use in those cases. However in the type of nonfiction I like to read, and the type I’d like to write, the primary attraction is insight: a novel and interesting idea well-argued and well-supported. For example, whatever the merits of my blog comment above, I’m at least putting forth a clear proposition supported by specific examples.

In contrast the AI-generated text seems more expressive than insightful—not surprising for a tool intended primarily for fiction writers—and doesn’t reference or cite any details in support of what the text is saying.

However, as cryptanalysts say of the task of breaking ciphers, “attacks always get better.” I have no doubt that GPT-3 is far from the final word on what AI systems can do for text, and that future systems will be significantly more capable of creating both fiction and nonfiction.

Leaving aside dystopic or utopic scenarios in which advanced AIs either exterminate humanity or enable us to live as gods, what does that mean for writers specifically? How might tools like Sudowrite and its future successors be used?

The current consensus view among people who’ve tried it is that different authors will likely use Sudowrite in different ways: some will use the wormhole feature to generate possible ways to continue a story, some will use the (experimental) “expand” feature to take outlines of scenes and generate example text to fill them out, others will use the “description” feature to give them ideas of how to enrich writing around characters and locales.

To my knowledge no one to date is using the system to auto-generate whole chapters, and at least one author (Leanne Leeds) who has tried a milder form of this reports that over-using the tool can lead to her feeling disconnected from her own writing. The preferred model is to become a “centaur,” a term from chess referring to players who make their moves in close consultation with a computer chess program, but do not simply turn the game over to the machine.

From my point of view as someone writing blog posts and other nonfiction, Sudowrite is still far from being generally useful. I had some hopes for using the “expand” feature in a nonfiction context, to fill out an argument where I had written the basic points. It didn’t work very well for this, either generating somewhat off-topic text or just repeating my own text back at me.

The “summarize” feature (also still experimental) may have more promise. It seems to work well for summarizing one’s own text (e.g., to see if key points are coming across), but when I tried to use it to summarize an entire academic paper (as a shortcut to reading the whole thing) it produced a “summary” that was multiple times the length of the original paper, repeating sections of summary text barely modified from one instance to the next.

In a spirit of fairness I’ll turn things over to Sudowrite to close out this post. First, a summary based on what I’ve written thus far (leaving out the sections where I talk about the AI-generated text). This definitely shows the current orientation of the service toward writing fiction:

The protagonist, a writer, is trying out the new service Sudowrite. The service promises to help people write better by getting them in touch with their creative side. The protagonist uses the service to generate possible dialogue and descriptions for a story. However, the AI has difficulty generating insightful writing.

And for the conclusion of the post, one of the alternatives generated by the wormhole feature that I thought worked best:

What does Sudowrite (and GPT-3 in general) mean for non-fiction writing going forward? I’m not sure yet. I do think there’s an important principle here, that given enough text of the same general type, even an AI system that isn’t exactly “aware” will begin to have instincts about what to do with that text.

There are a lot of interesting questions for any writer, but for a blogger in particular: What types of text am I writing, and how can I use AI systems to help me? How can I use AI systems to expand my capabilities—or “replace” me, if only partially and subtly—in writing?

The rising tide of AI-generated language will raise all writing boats, regardless of what is written. In turn those writers who are able to understand the AI-generated waves and surf them will gain a competitive advantage. I’m looking

Looking for what? It doesn’t say. I’ll finish the sentence myself: while I don’t think I’ll be signing up for Sudowrite in the short term, I’m looking forward to seeing what systems like this evolve into.

Further exploration

In case you’d like to read more about Sudowrite (or GPT-3):

- “The computers are getting better at writing” by Stephen Marche for _The New Yorker is the article that originally got me interested in Sudowrite, and is probably the best introduction for a general audience.

- An interview with Amil Gupta, one of the creators of Sudowrite, by author Joanna Penn. Gupta explains why he and co-founder James Yu decided to create Sudowrite, and how he sees the service being used.

- Author Leanne Leeds has an interesting series of blog posts describing how she tried to use Sudowrite when writing a new novel.

- The Alliance for Independent Authors issued a call for comments on AI for indie authors, to which one of the comments in response was from Amit Gupta. The call for comments was followed by an official ALLi statement “AI for Authors: Practical and Ethical Guidelines.”

- “Introduction to GPT-3” by Daniel Guterriez is a not-overly-technical summary of GPT-3 and related natural language processing systems.

And of course you can sign up for the private beta at the Sudowrite web site. It appears that the service is going to cost $20 per month after the free trial. (In comparison, the Grammarly service I mentioned above starts at $12 per month for the Premium version.)

In case you’d like more takes on Puella Magi Madoka Magica, here are some written completely by humans:

- “Kyubey’s Multi-Level Marketing Scheme: The Capitalist Metaphor of Madoka Magica” by Audrey Dubois for Anime Feminist. This essay is in the same general spirit as my blog comment, although I remain more cynical than her regarding the resolution of the plot.

- Nick Creamer’s review of episode 12 of Madoka Magica (part of his overall series of reviews) is a much more positive take on the ending of the series.

- A Google Scholar search for “Puella Magi Madoka Magica” returns a number of academic papers discussing the anime, some of which have full text available online without charge.

In the Unix family of operating systems “sudo” (“superuser do”) is a utility that you can use to run a command with enhanced privileges. Thus “Sudowrite,” a system that promises to let you “do writing” with “superuser” power. ↩︎