tl;dr: Let’s elect the Howard County Council in such a way that every voter has an equal chance to express their preferences and have them matter.

[This is part 3 of a seven-part series. See also part 1, part 2, part 4, part 5, part 6, and part 7. I also wrote a follow-up post that can be viewed as an alternative to part 5.]

In my first post I proposed a comprehensive overhaul of the way we elect the Howard County Council:

- Expand the council from five to fifteen members.

- Reduce the number of council districts from five to three.

- Elect five members in each district using ranked choice voting.

- Draw the district lines using an automated process overseen by an independent nonpartisan commission.

In this post I discuss why ranked choice voting is a better way to elect five members in each of the three proposed districts.

Why ranked choice voting?

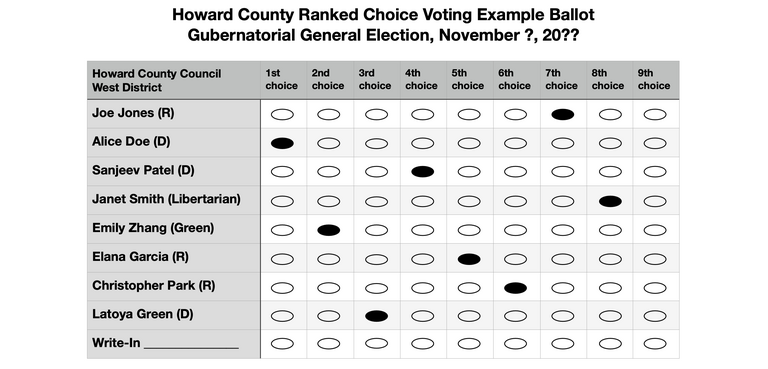

An example marked ballot for a hypothetical Howard County Council West District general election conducted using ranked choice voting. The voter has marked Democratic candidate Alice Doe as her first preference, Emily Zhang of the Green party as her second preference, Democrat Latoya Green as her third preference, and so on. (Click for a higher-resolution version.) Image by Frank Hecker; made available under the terms of the Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal (CC0 1.0) Public Domain Dedication.

If we want to have only three districts, with five members in each, and we don’t want to elect members using at-large voting within each district, how should we elect each district’s members? My proposal is to use ranked choice voting.

Using ranked choice voting in a multi-member district (like the three districts proposed here) helps ensure that elections are fair for all voters, and that each voter has an equal chance to make their votes matter. It allows voters the option to rank candidates in order of preference: one, two, three, and so forth. If a particular person’s vote cannot help their top choice win, that vote counts for their next choice.

The image above shows a sample ballot for a hypothetical Howard County Council election for the West District (as discussed in a future post) conducted using ranked choice voting. Here the voter, a progressive Democrat, indicated Democrat candidate Alice Doe as being her first preference, but then has marked Emily Zhang of the Green party as her second preference, ahead of the other Democratic candidates. She then marked Democrats Latoya Green and Sanjeev Patel as her third and fourth preferences, and then marked the other candidates as her fifth, sixth, etc., preferences.

Note that there is no requirement that the voter indicate a preference for all six candidates; she could have just stopped after marking her ballot for the three Democratic candidates and Emily Zhang. However, it may be that some of the Republican candidates are more acceptable to her than others, so she may want to give them preference ahead of other candidates. She may also dislike libertarians on general principle, so takes care to mark the Libertarian party candidate as least preferred.

(Note that there are only three Democratic candidates and three Republican candidates on the ballot. You may wonder, why wouldn’t the two parties put forth five candidates each, given that there would be five open seats? That’s because in ranked choice voting it doesn’t make sense for a party to put more candidates on the ballot than that party’s expected share of voters would warrant. I’ll discuss this in more depth in a future post, but will note for now that in this example district Democrats and Republicans are evenly matched.)

In a five-member district like the hypothetical Howard County West District in this example, there would be a 16.7% “quota” for election.1 If more than 16.7% of ballots cast marked a particular candidate as their first preference then that candidate would be automatically elected. Any of those votes that they received from voters in excess of the quota would be transferred to other candidates, more specifically the candidates named by their voters as their second preferences.2

In our example suppose that Democratic candidates Alice Doe and Sanjeev Patel had enough first preference votes to win outright in the first round of county. (In other words, they both got more than a 16.7% share of all first preference votes cast.) If enough Doe or Patel voters followed our example voter and indicated a second preference vote for Emily Zhang of the Green party, the excess votes for Doe and Patel (i.e., above the quota) could help elect Emily Zhang in the second round of counting, after all excess voters were transferred to other candidates.

More specifically, if Zhang did not have enough votes in the first round of counting to exceed the quota, she might have enough votes in the second round to exceed the quota, by virtue of votes transferred to her because Alice Doe and Sanjeev Patel didn’t need the votes, and their voters marked Zhang as their second preference. Zhang would then be deemed elected in the second round of counting. (The colloquial term for this is “getting in on transfers.”)

Other candidates could benefit from this as well. For example, if Republican Joe Jones were elected with first preference votes in the first round of counting, and he were the only Republican candidate to be elected in that first round, his excess votes (above the quota) could end up being transferred to Elana Garcia or Christopher Park.

On the other hand, suppose that after excess votes from the first round were transferred to other candidates, there were still no candidates with votes in excess of the 16.7% quota. In that case the candidate with the least amount of votes would be eliminated, and their votes would be transferred to others according to their voters’ preferences. So, for example, if Emily Zhang were in last place after the second round of county, any votes assigned to her after the first round would be transfered to other candidates (probably Democratic candidates) heading into the third round of counting.`

Vote tabulation would proceed in this manner round by round, transferring votes from successful candidates to other candidates, and eliminating last place candidates, until five candidates were elected. (The way in which the quota is defined makes it impossible for more than five candidates to be elected.)

(In some cases voters may not rank all candidates. For example, the voter in the example above may indicate her preferences for Emily Zhang, the Green party candidate, and the three Democratic candidates, but may not indicate her preferences regarding the Republican candidates and Janet Smith, the Libertarian candidate. If so, her ballot will not be considered further once Emily Zhang and the three Democratic candidates are either elected or eliminated; at that point the ballot is said to be “exhausted.”)

Promoting political and ideological diversity

In addition to allowing voters to rank candidates from the two major parties according to the voters’ preferences, ranked choice voting also allows voters to vote for third-party candidates without “wasting” their vote. This can be seen in the example above: even if Emily Zhang was eliminated in the second round of counting, the expressed preferences of voters like our example voter could end up helping to elect other candidates in the third or subsequent round.

As another example, suppose that there were a third party associated with the Democratic Socialists of America. That party could run a DSA-backed candidate in a council district with lots of progressive voters, and encourage those voters to give that candidate their first preference. If the DSA-backed candidate were unsuccessful then their first-preference votes would simply transfer to the candidate (most likely a progressive Democrat) that those voters had marked as their second preference, and could then help that candidate be elected.

The same logic works for independent candidates. For example, if a “Never Trump” conservative couldn’t make it through the local GOP primary then they could run for a county council seat as an independent. If their popularity were high enough then they could potentially attract enough first and second preference votes to be elected in their own right. As with the DSA example above, a Republican voter giving such a candidate their first preference would not be “throwing their vote away,” since they could—and presumably would—designate the official Republican candidates as their second, third, etc., choices.

Promoting racial and ethnic diversity

The same dynamic works for promoting racial and ethnic diversity on the council. For example, a Black Democrat running for the council in a district could appeal to Black Democratic voters to give the candidate their first preference votes, and then to give other Democratic candidates their second preference votes. Such a candidate might also attract second or third preferences from conservative Black voters who might give their first preference votes to Republican candidates.

This would allow Black candidates to leverage Black voter support in all three districts, as opposed to having Black voters be concentrated in a single district.

Similarly, a Korean-American Republican candidate might get first preference votes from Korean-American Republican voters, second preference votes from other Republican voters, and second or third preference votes from Korean-American independents or even Democrats who wanted to see some Korean representation on the county council.

To repeat, in none of these cases would voters be “wasting” their votes on a candidate with marginal prospects. They could vote according to their own heart’s desires, secure in the knowledge that their preferences would be reflected in the final results one way or another.

So, let’s assume that we have three council districts with five members each, and that we’d elect those members using ranked choice voting within each district. How could we draw district lines in a way that would reflect the racial, ethnic, and political diversity of Howard County, be open and transparent, and could be justified to the voters and candidates who participate in the resulting elections? That will be the topic of my next post.

For further exploration

For more on the topic of ranked choice voting see the following:

- FairVote is an advocacy site for ranked choice voting. Its recent report “Ranked Choice Voting Elections Benefit Candidates and Voters of Color” and its analysis of the use of ranked choice voting in the 2021 New York City primaries are particularly relevant to my comments above regarding promoting more diversity on the Howard County Council.

- The Ranked Choice Voting Resource Center has more in-depth information, including a detailed discussion of issues relevant to election administrators.

For a more detailed discussion of how ranked choice voting might work in the context of a Howard County Council election, see my 2012 post “Electing a council that reflects Howard County, part 1” and its followup post. These were written for the case of electing the five current Howard County Council members by ranked choice voting, but they are also relevant to the problem of electing five council members in a single district of the proposed three. (Note that the posts refer to ranked choice voting using the alternative name “Single Transferable Vote” or “STV.”)

The 16.7% is an approximation. The actual quota would be one-sixth of the total votes cast, plus one (rounded up). ↩︎

The exact way in which these transfers are done can vary depending on the counting procedures adopted. The specific mechanisms selected can be embodied in the software used to tabulate votes. ↩︎