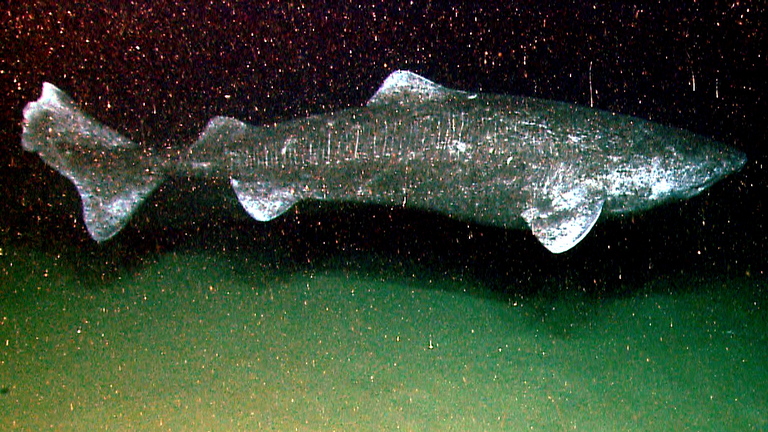

A Greenland shark (Somniosus microcephalus). With an average lifespan of about 400 years, some are about as old as Harvard. Click for a higher-resolution version. Image in the public domain.

[This post was originally published on Cohost. It has been slightly revised from the original.]

This post—and some future ones as well—was prompted by a book I once read about the prospects for creating a new university, as well as by general comments I’ve read about admissions policies at elite universities. Since I am decidedly not an expert on issues of higher education, I decided to approach this from the other direction: as a naïve observer doing a “spherical cow” analysis (as physicists like to call it), abstracting away all the complexity and seeing what results from analyzing a problem in as simple terms as possible.

Canadian higher education expert Alex Usher once referred to elite universities as the “apex predators” of the academic world, based on their continued appearances at the top of world rankings. With that in mind, let’s look at Harvard in particular, one of the best known and most elite universities, and consider it as we would a biological organism. What are its main characteristics, and how does it survive?

Harvard lives despite things that could kill it

First, considered as an organism the most notable characteristic of Harvard is how long-lived it is: nearly four hundred years old at this point. (And it is still relatively young in comparison to others of its species; Oxford and Cambridge are both almost a thousand years old.)

From this fact we can conclude that the first and foremost priority of Harvard is to ensure its own survival. If this were not the case then Harvard would likely have ceased to exist by now, as pursuing other priorities would have endangered its quest to survive.

What are the most important threats to Harvard’s survival? They are arguably financial reverses, political reverses, and cultural reverses:

Financial reverses, either local to itself or in the broader economy, could cause Harvard to go bankrupt and force its closure. Consistent with its long lifetime, Harvard must plan for possible financial reversals of a scale that might occur only once every couple of hundred years.

What about political reverses? These are potential government actions that would threaten Harvard as an institution. This might include, for example, taxing Harvard’s endowment or otherwise financially penalizing the university, forcing it to modify its admissions policies (see below), or otherwise interfering with the relative independence Harvard enjoys as a private university that is (mostly) privately funded.

Finally cultural reverses would threaten Harvard’s status as “Harvard”, its reputation as a world-leading university that others might seek to emulate in their own countries or regions (“the Harvard of X”) but can never equal, much less surpass. Harvard is vulnerable to such reverses because in some ways it is like Kim Kardashian and similar celebrities: to a nontrivial degree it is “famous for being famous”.

Harvard’s defenses

How does Harvard protect itself against such reverses? We can analyze this by again looking at Harvard as if it were an organism. To survive an organism takes in food, creates protein products and other structures to build and maintain the body it needs to survive in a hostile environment, and excretes whatever is excess to that function.

From that point of view, Harvard’s “food” is the very large group of people (over sixty thousand per year) striving to be admitted to Harvard. It uses that “food” to create the visible structures that people think of when they think of Harvard (the buildings and faculty), to create a store of “fat” for times of potential starvation (its endowment), and to build an “extended phenotype” consisting of the Harvard alumni network, the much smaller group of people (less than two thousand per year) who go out into the world with “admitted into Harvard” stamped on their foreheads. (I write “admitted into Harvard” instead of “graduated from Harvard” because, as examples like Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg illustrate, arguably the important thing is getting into Harvard, not graduating from it.)

(Under this analogy, research results can be considered as Harvard’s excreta: the things it throws off as it survives as an institution down the years, and that have fertilized many fields.)

For purposes of this analysis I focus on the Harvard alumni network. How does it help Harvard address the threat of the various possible reverses discussed above?

The threat of financial reverses can be addressed by having Harvard alumni whose financial success can translate into donations to help Harvard maintain and grow its endowment. That endowment is currently over USD 50 billion; it provides about 36% of Harvard’s annual revenue, or over USD 2 billion a year.

USD 50 billion sounds like a lot of money, and it is; it’s the largest endowment of any US university. But that endowment needs to be so large because it needs to cover very rare “black swan” financial disasters. I’m sure that the folks who run Harvard would be happy to see it be two or three times its current size, if not larger.

The threat of political reverses can be addressed by having a large contingent of Harvard alumni in the legislative, judicial, and executive branches of government who are sympathetic to Harvard and who can be relied upon to block or water down any government actions that might disadvantage it.

Finally, the threat of cultural reverses can be addressed in a similar way, by having a large contingent of Harvard alumni in key cultural institutions – leading newspapers, magazines, publishers, and so on – that have the power to confer cachet upon Harvard and those associated with it.

Explaining the Harvard admissions process

Now, the above is nothing more than a cute and overly clever analogy unless it has some degree of explanatory power. So, given the above, what can we conclude about Harvard, and in particular about its key function, that of creating a select set of Harvard alumni?

First, to counter potential financial reverses Harvard needs to build an alumni population that is willing and able to financially support it in a major way, so that its endowment can grow ever larger. This can be done by preferentially taking in applicants who are wealthy already, or likely to be wealthy in future.

Harvard has at least three strategies available by which to do this: it has a “farm system” of exclusive (and expensive) prep schools whose staff have deep and enduring relationships with the Harvard admissions department, it gives preferential treatment to the children of Harvard alumni (“legacies”), and it can also of course just admit the children of major donors. The overall result is to build a pool of alumni who have benefited from special treatment in admissions, who are inclined to “give back” to Harvard in return, and who will have the financial means to do so.

Second, to counter potential political reverses Harvard needs to build a supportive network of legislators, judges, and executive branch senior leaders. Since most such figures are lawyers (by definition true for judges, and almost as true for legislators), it’s obviously key for Harvard to have a strong law school. But perhaps equally if not more important, Harvard needs to have a feel for which groups within American society have political power (or at least political influence) and then ensure that it admits students from such groups in proper proportion to such power and influence.

To put it in a more negative way: if (to pick a fictional example) Graustarkian-Americans have relatively little power or influence in the US political system, then Harvard has less incentive to admit them as students, even if they otherwise form a relatively large percentage of qualified applicants. Harvard would likely instead preferentially admit students from other groups with more political clout.

Finally, to counter potential cultural reverses Harvard needs a similar supportive network of journalists, public intellectuals, and other media figures at major cultural institutions. The presumed mechanism here is to put much more emphasis on admitting students who are verbally skilled and culturally fluent at the expense of students who are more STEM-focused.

To put it more bluntly, Harvard is not CalTech, and does not want to be; its place in American culture as the ultimate university experience is exemplified by Elle Woods in Legally Blonde, not by Sheldon Cooper in The Big Bang Theory. (It’s worth noting here that the original novel Legally Blonde is set at Stanford; presumably the people who made the movie felt that using Harvard as the setting would resonate more with the typical viewer.)

Harvard forever

Given the above, what predictions can we make about Harvard’s future, particularly with respect to its admission policies?

First, I predict that Harvard will not follow the urgings of those who advocate it doubling or even tripling the number of students it enrolls (presumably in order to give more students the “Harvard experience”.

Part of the reason is by analogy to long-lived organisms (like the Greenland shark pictured above), which have long lives in large part because their metabolism is very slow. Even a very low rate of growth in enrollment would cause Harvard to balloon to an enormous size when extended over a few hundred years. Another reason is that increased enrollment would put more pressure on the endowment, should it become necessary to draw it down during hard financial times.

But I think the most important reason is that the pool of suitable positions for Harvard alumni is limited, and will remain so: There are only 535 Senate and House seats, less than a thousand Federal judgeships, only so many jobs at presitigious investment banks and private equity firms, and similarly only so many positions at leading newspapers, magazines, and related cultural institutions. Given that, increasing the number of Harvard alumni (a form of “elite overproduction”) would only increase the already intense competition for those positions, with little or no benefit to Harvard itself and its ability to survive as an elite university.

Second, I predict that Harvard will not change its admissions policies in any major way (for example, by instituting a lottery for admittance), and will not be forced to do so by US courts or legislatures. (As, for example, is at stake in a case currently before the US Supreme Court.) As I argue above, Harvard’s long-term survival depends on its having the freedom to tailor its student body to address potential financial, political, and cultural threats. I believe that its political and legal support network is strong and motivated enough to ensure that it retains that freedom.

Finally, if Harvard by some chance is forced to modify its admissions policies, I predict that it will attempt to accomplish its previous goals by different means. For example, it would likely further de-emphasize criteria such as test scores, grades, and student background (race, ethnicity, class, etc.), and put even more emphasis on student personality, ability to fit into the Harvard environment, recommendations from alumni, general “promise”, and other intangible aspects used to assess an applicant’s suitability to be a “Harvard person”. (In other words, Harvard’s admissions process would become even more opaque than it already is.)

Harvard has survived nearly four hundred years by doggedly pursuing its own interests and acting to neutralize potential threats to its survival. I would not bet against its ability to survive four hundred more.