[This post originally appeared on Cohost.]

Recently I stumbled across a blog post by Julian Gough. His post is both long and heartfelt, but the bare facts are follows:

Upon being solicited by Minecraft developer Markus “Notch” Persson, Gough agreed to write a text—the End Poem—to be displayed to players who beat the game in survival mode. After much back and forth, Persson’s company Mojang paid Gough GBP 20,000 for his work, but never got a formal copyright assignment, Gough having rejected the proposed contract as being too one-sided and not respecting his role as the writer.

Before the acquisition of Mojang by Microsoft was announced, Mojang executives again approached Gough to try to get him to sign a formal contract, but he again refused. Eventually after much agonizing—and some resentment of the financial rewards realized by Persson and others at Mojang—Gough decided to waive any rights he had with respect to the End Poem and dedicate it to the public domain.

There is much in this saga that touches on the topic of art vs. business; at its core it is a story of someone who thought he was an artist creating art trying—and failing—to communicate with people who thought they were businesspeople creating a product. But that topic is too big for me to discuss right now; instead I’ll focus on the reaction to Gough’s story, and then on the poem itself.

I’ll start with the commenters at Hacker News. I’ve been on the Internet a long time (back to the Usenet era), and am quite aware of the negativity that can be found there; however, I was taken aback at the intensity of the contempt directed at Gough. The various reactions can be paraphrased as follows:

“Gough is a nobody, he had nothing to do with the success of Minecraft.” “Gough got his money, then got greedy for more.” “I am not a lawyer, but here is my confidently-expressed argument that Gough didn’t have a legal leg to stand on.” “Gough probably didn’t spend more than a couple of hours writing that, it wasn’t worth 20,000 pounds.” “Gough wasn’t Notch’s friend, he was just a contractor.”

I find these last two classes of comments particularly interesting and ironic. The first is essentially an expression of the labor theory of value: that the economic value of an item should depend on the amount of work that went into producing it—hence the claim that Gough was grossly overpaid for (supposedly) a few hours work. But this claim applies with much greater force to Persson, who realized USD 1.5 billion in financial rewards for just a few years of work. Even if he worked 100 or more hours a week, that still equates to an hourly wage of about USD 50,000, an order of magnitude or two greater than what we’d expect to pay even a top-rank programmer.

Similarly, one of the commenters claimed that Gough had a “parasocial relationship” with Persson, thinking Persson was a friend when he was instead an entrepreneur looking for a hired hand. But it seems to me that many of the Hacker News commenters themselves have a parasocial relationship with the founders, VCs, and rockstar developers who form the elite of the technology industry.

They eagerly consume their idols’ blog posts and tweets, vociferously defend them from criticisms both large and small, and think themselves knowledgeable about the startup world and everything connected to it, so that if they were ever handed a term sheet they would be able to negotiate a Series A round as deftly as those whom they idolize. But I suspect that if the actual founders, VCs, and other power players were ever to come into contact with most Hacker News commenters, they would dismiss them as “Internet randos.”

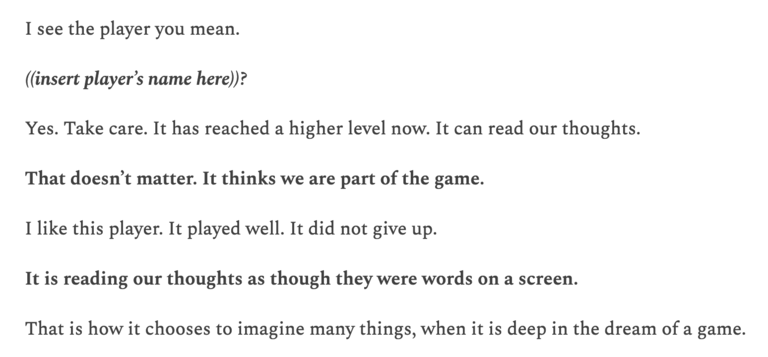

Enough of Hacker News. If we turn to Gough’s blog post, we find an entirely different set of commenters, almost all expressing gratitude to Gough for both writing the End Poem and setting it free, with many telling him that the End Poem changed their lives. So it behooves us to look at the End Poem itself, a copy of which Gough appended to his post (and the beginning of which is shown above).

Strictly speaking, the End Poem is a prose poem: part story, part poem. It has enough poetic aspects that I will consider it—and judge it—as I would a poem. I’ve read much more poetry than the average person, have concentrated my reading among those considered “major poets” in the literary canon, and as a consequence have pretty high standards for what I consider a good poem (or prose poem).

So one might expect me to unfavorably compare the End Poem—an appendage to a “mere” video game—to “real” poems (such as one might find in the New Yorker or Poetry magazines). Or, if I were to acknowledge any excellence at all about it, to dismiss it with a variant of Noel Coward’s comment about the potency of “cheap music.”

But I’m not going to do that. As poetry the End Poem is as suited to its context, and to its audience, as are the poems that appear in the New Yorker or Poetry, and it seems to have meant far more to at least some of those who played Minecraft than the typical New Yorker or Poetry poem does to its readers. Why is that?

The End Poem does two things, and does them both very well. Recall its original context: it was shown only to players who had successfully completed the game. Those players would likely have spent dozens of hours attempting this, during which they would risk becoming estranged from the outside world, including their family and their friends. Some might have started playing Minecraft because they were already estranged from their family or others, and sought refuge from that estrangement in the game.

To those people, the End Poem first says: You have not wasted your time playing this game. This game—this “world that was flat, and infinite [where] the sun was a square of white”—is no less real—and no less worthy of your and our attention—than anything in the supposedly “real” world.

But it also says that likewise this other world—“on the thin crust of a spinning globe of molten rock”—is no less real than the world of the game, and that the player who is about to leave the game can achieve their goals in this world just as they have in that world:

and the universe said I love you and the universe said you have played the game well and the universe said everything you need is within you and the universe said you are stronger than you know

The length of the End Poem, and the nine minutes or so it takes to display, serve as a decompression chamber for players, to prepare them before they leave the world of the game to reenter the other world. That process culminates in the most famous affirmation in the End Poem:

and the universe said I love you because you are love

William Blake wrote, “You never know what is enough unless you know what is more than enough.” That line in the End Poem teeters on the edge between enough and more than enough, and even goes a bit over the edge (as Gough himself acknowledges), but I understand why Gough left it in, and why it meant so much to so many people.

As I see it, it says to the player: you can love, and you can be loved. The love you put into playing this game is a mirror of the love you can put into living your life and being with others, and if you do that then that love can and will be returned to you.

And the game was over and the player woke up from the dream. And the player began a new dream. And the player dreamed again, dreamed better. . . .

You are the player.

Wake up.

And now, thanks to Gough, the End Poem is now part of our common heritage from which future artists can create more works of art. And Gough himself has seen his act of generosity been repaid by people subscribing to his newsletter and potentially buying his next book.

But what about all the other artists, the ones whose work languishes in obscurity or was sold for a mess of pottage in work-for-hire arrangements? Gough touches on their plight in his post, and has things to say about it. And so will I.