[This post and its associated comments were originally published on Cohost.]

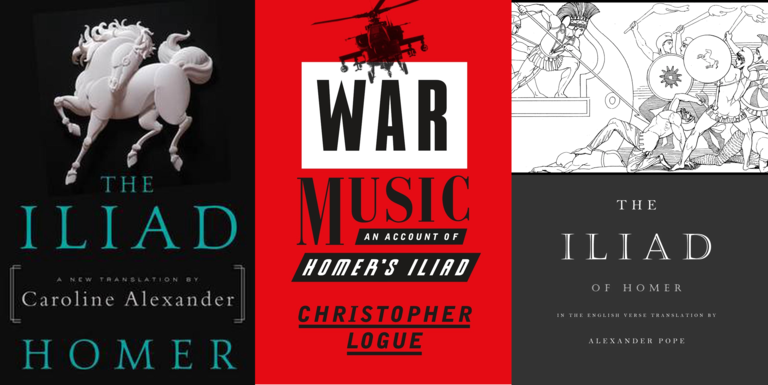

Prompted by a book post by @JhoiraArtificer, I got a copy of the Maria Headley translation of Beowulf, which I greatly enjoyed. In a comment on that post I recommended Christopher Logue’s free translation/adaptation of Homer’s Iliad, contrasting it with more conventional translations. I’ve started reading Caroline Alexander’s translation of the Iliad, one of the more heralded modern translations, and thought it might be fun to present it side by side with Logue’s version, along with a classic translation, that of Alexander Pope.

Im my comment on the book post I noted that there are two ways to translate Homer. To expand on this: The first is to attempt to fully translate the original Greek, replicating all the nuances of word choice in the original. Having done that, then try to make the result read as poetry, and in particular as much like Homeric poetry as possible—keeping in mind that metrical conventions in ancient Greek were not the same as in modern English.

Caroline Alexander’s 2015 translation is a good example of this first choice. In the introduction to her translation, she explains how she went about translating the Iliad:

My approach has been to render a line-by-line translation as far as English grammar allows; my translation, therefore, has the same number of lines as the Greek text and generally accords with the Greek lineation. I have tried to carve the English as close to the bone of the Greek as possible. The translation is in unrhymed verse, with a cadence that attempts to capture the rhythmic flow and pacing, as well as the epic energy, of the Greek, and which like the Greek varies from verse to verse. It is meant to follow unforced rhythms of natural speech.

Here is how her translation starts:

Wrath—sing, goddess, of the ruinous wrath of Peleus’ son Achilles, that inflicted woes without number upon the Achaeans, hurled forth to Hades many strong souls of warriors and rendered their bodies prey for the dogs, for all birds, and the will of Zeus was accomplished; sing from when they two first stood in conflict— Atreus’ son, lord of men, and godlike Achilles.

This is serviceable enough, but with some clunkiness that was presumably unavoidable given that Alexander wished to keep the word choices and line numbering the same as the Greek original. The appended “for all birds” is especially jarring and unnatural.

The poem then sets up the basic setting and conflict of the first book of the Iliad: the Greeks (“Achaeans”) have been at war many years at Troy, but are still stuck on and near the beach, unable to advance beyond it. Agamemnon (“Atreus’ son”), the paramount king of the Greeks, has taken for himself a girl captured as a slave, Chryseïs, the daughter of Chryses, a priest of the god Apollo. Chryses tries to ransom her, Agamemnon refuses to return her, Chryses prays to Apollo to punish the Greeks, and Apollo sends a plague unto them. Another priest tells Agamemnon that to stop the plague he must return Chryseïs to Chryses, and he agrees to do so, but in recompense he takes Achilles’ favorite captured slave girl, Brieis. This angers Achilles to no end, and after bitching about it to Agamemnon he also complains to his mother, the sea nymph Thetis:

But Achilles,

weeping, quickly slipping away from his companions, sat

on the shore of the gray salt sea, and looked out to depths as dark as wine;

again and again, stretching forth his hands, he prayed to his beloved mother:

“Mother, since you bore me to be short-lived as I am,

Olympian Zeus who thunders on high ought to

grant me at least honor; but now he honors me not even a little.

For the son of Atreus, wide-ruling Agamemnon

has dishonored me; he keeps my prize, having seized it, he personally taking it.”

This, to me, does not read like poetry; to quote a phrase I read somewhere on Twitter in another context, it is “lineated prose.” The requirement to match the original line for line has forced some lines to be over-long, breaking the flow of the poem.

As I said, it’s a serviceable translation, but I’m wondering how far I’ll be able to get through it. (In fairness, this approach does have its advocates; see for example this enthusiastic review of Alexander’s translation.)

The other way to approach the Iliad is to remember that you’re creating a poem for general readers in your own time, not for ancient Greeks or classicists. The approach here is ignore the letter of the Iliad and to imbue it with spirit—which may not actually be the spirit as perceived by its readers in antiquity, but a spirit that resonates with contemporary readers, whose background and mindset are entirely different.

Thus we turn to Christopher Logue’s partial adaptation of the Iliad, published from 1991 to 2003 and collected in two books, War Music and All Day Permanent Red (a wonderful title, that one). Logue describes his own approach as follows, in the introduction to War Music:

Rather than a translation in the accepted sense of the word, I was writing what I hoped would turn out to be a poem in English dependent on whatever, through reading and through conversation, I could guess about a small part of the Iliad . . . . My reading on the subject of translation had produced at least one important opinion: ‘We must try its effect as an English poem,’ Boswell reports Johnson as saying; ‘that is the way to judge of the merit of a translation.’

Logue assumed that his readers knew the basic plot and characters of the Iliad, and thus he could skip the setup and the introductions. He presumably also knew that lazy reviewers judge the quality of an Iliad translation based on its famous first lines, and often don’t read much further than that. Logue violates that expectation by beginning in media res, as the unnamed Achilles leaves his tent to complain to his (also unnamed) mother:

Picture the east Aegean sea by night,

And on a beach aslant its shimmering

Upwards of 50,000 men

Asleep like spoons beside their lethal Fleet.

Now look along that beach and see

Between the keels hatching its western dunes

A ten-foot-high reed wall faced with black clay

And split by a double-doored gate

Then through the gate a naked man

Whose beauty’s silent power stops your heart

Fast walk, face wet with tears, out past its guard

And having vanished from their sight

Run with what seems to break the speed of light

Across the dry, then damp, then sand invisible

Beneath inch-high waves that slide

Over each others’ luminescent panes;

Then kneel among those panes, beggar his arms, and say:

“Source, hear my voice.

God is your friend. You had me to serve Him.

In turn, He swore: If I, your only child,

Chose to die young, by violence, far from home,

My standing would be first; be best;

The best of bests; here; and in perpetuity

And so I chose. nor have I changed. but now—

By which I mean today, this instant, now—

That Shepherd of the Clouds has seen me trashed

Surely as if He sent a hand to shoo

The army into one, and then, before its eyes,

Painted my body with fresh Trojan excrement.

Logue was not the first poet to “go wild” with Homer. In 1715 the young poet Alexander Pope, after making a name for himself with his first works, kicked off an audacious project to publish a new English translation of the Iliad using his favored poetic form, heroic couplets. (Pope’s was the second translation to English, the first being that of George Chapman over a hundred years before.)

Here are the opening lines; note that Pope uses the Roman names for the gods, not the Greek ones:

The wrath of Peleus’ son, the direful spring Of all the Grecian woes, O Goddess, sing! That wrath which hurled to Pluto’s gloomy reign The souls of mighty chiefs untimely slain, Whose limbs, unburied on the naked shore, Devouring dogs and hungry vultures tore: Since great Achilles and Atrides strove, Such was the sovereign doom, and such the will of Jove!

Contrast Alexander’s “rendered their bodies prey for the dogs, for all birds” with Pope’s “whose limbs, unburied on the naked shore / Devouring dogs and hungry vultures tore.” Fidelity to the Greek be damned, I can’t imagine anyone preferring Alexander to Pope here.

Again, for contrast, here is the section where Achilles leaves his tent to appeal to Thetis:

Not so his loss the fierce Achilles bore,

But sad retiring to the sounding shore,

O’er the wild margin of the deep he hung,

That kindred deep from whence his mother sprung;

There, bathed in tears of anger and disdain,

Thus loud lamented to the stormy main:

“O parent goddess! since in early bloom

Thy son must fall, by too severe a doom;

Sure, to so short a race of glory born,

Great Jove in justice should this span adorn;

Honour and fame at least the Thunderer owed;

And ill he pays the promise of a god,

If yon proud monarch thus thy son defies,

Obscures my glories, and resumes my prize.”

A contemporary of Pope’s remarked, “It is a pretty poem, Mr. Pope, but you must not call it Homer.” I don’t care whether we call it Homer or not, it’s a pretty great poem; I read the whole thing, all thousand-plus pages of it. Pope’s contemporaries agreed with me; the translation netted Pope the equivalent of several hundred thousand dollars in today’s currency. Nobody remembers the name of the person who criticized it.

Vince Hancock (@vhhancock) - 2023-01-08 20:31

What a great essay about the problems of translation. Thank you. I’m making my way through Pope’s version now. His footnotes are making it a richer experience.

Frank Hecker (@hecker) - 2023-01-09 12:57

Thanks for commenting! I actually think Pope’s version is the one version I was able to read all the way through; at least, it’s the only one I have on my bookshelf, and I don’t recall reading any other versions.

Iro (@Iro) - 2023-01-08 20:35

I’ve been enjoying Super Bunnyhop’s goofy audiobook Iliad project so far. https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLgdySZU6KUXLVEyoi0IuQN7vlkVFTAKse

Frank Hecker (@hecker) - 2023-01-09 12:59

Thanks for commenting! I checked out the first episode of this. It was a pretty cool undertaking, almost like a Homeric radio drama. I could definitely see listening to this in the car while commuting, if I still actually commuted to work.

stylo (@stylo) - 2023-01-09 14:07

I find that pope translation unbearable, indelibly stamped with the cultural hallmarks of British colonialism of that era. I have the Lattimore on my shelf

Frank Hecker (@hecker) - 2023-01-09 17:47

Thanks for stopping by to comment! The Pope translation is definitely of its time, no question. I don’t have the Larrimore, but I’m going to try a read-through of the Caroline Alexander translation once I finish reading Logue. (There’s something to be said for getting the whole story and not just the highlights.)

Mightfo (@Mightfo) - 2023-01-12 22:23

Thanks for sharing! It can be frustrating how people dont understand that there is no such thing as direct translation for anything sufficiently complicated- flow and nuanced meaning and structure all combined to make 1:1s completely impossible, and poetry is a nice way to convey this impossibility, partially since conveying the impossibility of mapping meaning and impact in prose is more difficult, less obvious.

That’s quite an enormous gap between Caroline Alexander’s translation and Logue/Pope’s translations. It may be illuminating to compare to another as well that is not as “not quite a translation” as Logue/Pope’s but takes fundamentally different tradeoffs compared to Caroline Alexander’s.

http://emilyshauser.weebly.com/news/a-step-by-step-guide-to-the-translations-of-homers-iliad This is nice, and the “Greekness” notion with Robert Fitzgerald’s is intriguign. Also, the book cover translations are fascinating- a photo of D-day for Lombardo’s?! Logue’s struck me similarly.

Frank Hecker (@hecker) - 2023-01-13 20:08

As always, thank you for commenting! I confess I haven’t read any of the Iliad translations by Lattimore, Fagles, Fitzgerald, etc., so I can’t comment intelligibly on them. I have however read both Fagles’ and Fitzgerald’s translations of the Odyssey, and recall liking them. The Odyssey is a very different poem than the Iliad, though.

Mightfo (@Mightfo) - 2023-01-13 21:28

Re: confess: No worries/surprise, I only read one translation back in university myself and lightly looked at a few others, haha. I bet theres some interesting articles giving a dive into that sort of comparison anyway.