[This post and its associated comments were originally published on Cohost.]

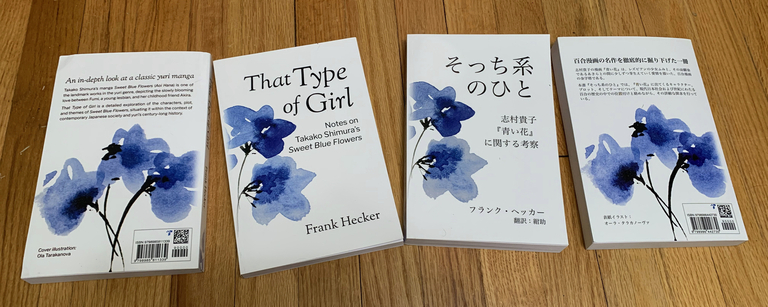

Today is the one-year anniversary of my publishing my book That Type of Girl: Notes on Takako Shimura’s Sweet Blue Flowers. As it happened, about a month ago someone who read the book sent me a nice note about it. That prompted me in turn to revisit the book and reread several chapters in it, and in the course of doing that I discovered one typographical error in the English edition and a missing footnote in both the English and Japanese editions. (Hence the title of this post.)

Fortunately I still had about three days left on the license for the software I used to create the print versions, so I was able to make the changes and push the revised versions out to my own web site and to the various online bookstores I used for commercial distribution. I suspect that these will be the final changes I make, and now that it’s been a year since publication I thought it was also a good time to post my final thoughts on the book itself and the process of creating it. Even if you’re not interested in this particular book, if you’ve ever thought of writing and self-publishing a book yourself then this may be of interest.

Why write a book?

Writing a book takes an order of magnitude or more time than writing a blog post, or even a series of blog posts. So anyone thinking about doing it needs to answer the question, “why do I want to do this?” In my case I had already done a series of Tumblr posts about Sweet Blue Flowers, so I had to justify to myself why I should put in the effort to turn it into an actual book.

The first reason is that I wanted to explore in more depth some of the questions that came to my mind while writing my Tumblr posts. Some of these were questions about the historical background of the yuri genre: Why were so-called “S” relationships between schoolgirls, and “S” literature about such relationships, so prevalent in Japan in the first half of the twentieth century? Why did those relationships and that literature almost completely disappear in the second half of the twentieth century? And why did “S” literature seemingly reappear in the early twenty-first century in the form of Maria Watches Over Us and its successors, including Sweet Blue Flowers?

Others were questions about Sweet Blue Flowers itself: Why does it start the way it does? Why do Fumi and Akira act the way they do? What about Yasuko and Kyoko? Is there any special significance to the plays that Shimura features in the various school years and, if so, what is it? And my personal favorite: Why are there so many scenes relating to urination and incontinence?

I was able to come up with plausible (at least to me) answers to almost all of my questions. In some cases, as with questions about the rise and fall of S literature, I rediscovered or recapitulated answers already put forth by academics (including Yukari Fujimoto in particular), but I tried to add some additional context. In other cases, including questions about Sweet Blue Flowers, I haven’t seen my proposed answers echoed anywhere else—which of course could equally mean that I’m clever or a fool. I won’t comment any more here on my proposed answers; you can read the book if you’re curious.

The second reason I decide to write a book was because I wanted to explore the process of creating and publishing a book in more depth. I had previously written and published a book of purely local interest, but only as an ebook. I wanted to create an actual paperback book with better typography and cover art, and go through as many of the steps of “real” publishing that I could, within the constraints of my time and budget.

Note that I did not write the book expecting anyone to read it, much less pay me money for it. I wrote it for myself, and anything beyond that is a bonus.

Researching and writing the book

Prior to writing the book I was generally familiar with the history of the yuri genre and its “S” literature predecessor, but had huge gaps in my knowledge about Japanese history and society relevant to that history. And, of course, I didn’t then and still don’t know Japanese at all.

Fortunately there is a small but fairly active group of academics who have published extensively in English on topics relevant to the book, and I took as much advantage of their expertise as I could. I now have more than twenty books on my bookshelf that I bought in the course of researching my own book, and several more that I bought in Kindle format. Other books had open access copies available, made available either by the authors or the publishers, and a few were available on the Internet Archive for temporary borrowing.

Academic papers were a separate issue. A lot of papers are paywalled and are available from journal publishers only at extortionate rates ($20 per paper or even more). (It’s often cheaper to buy a book that’s an edited collection of papers, even if only a couple of papers are of interest.) Fortunately, as with books, many authors and even some publishers make copies available at no charge. Some judicious Internet searching in various places found the few remaining ones I needed.

When it came to the actual writing of the book I wanted it to adhere as closely as possible to academic conventions, including doing formal citations and a full bibliography. My guide to doing that was the Chicago Manual of Style (17th edition), which I highly recommend. It’s available online as a subscription service, but I recommend getting the hardcover book; it’s handier to use if you consult it often, and you can sometimes find it available at 50% off during sales at the publisher’s website.

The good: The Internet and all the services it supports (Google Scholar and general Internet search engines, the Internet Archive, Amazon and Abebooks, etc.) put doing research like this within reach of the typical interested person, especially if you’re willing to spend a little money. The bad: academic publishing is a rip-off, and it’s no wonder that many people (including academics themselves) are turning to pirate sites to get copies of papers.

Formatting and publishing the book

As I noted previously, my first book was published as an ebook only. Because I wanted to learn how ebooks worked at a low level, I actually hand-coded the entire book in (X)HTML. That was not an option for this book, since I also wanted to create a PDF version that I could use to publish a paperback version. But I still wanted to work with a text-based format, so I could put the book under version control in a source repository, as opposed to creating Microsoft Word documents—the typical format used by self-publishers today.

Fortunately I was able to find an almost free solution in the Electric Book software suite, built on a variety of free and open source software products. The only software I had to pay for was the Prince XML software used to create the PDF version, and the image processing software I used for the cover art (see below).

The Electric Book software enabled me to write in Markdown format, which I also use for my blog, while still having fairly tight control over the formatting of the book in both PDF and EPUB3 versions (although for the most part I went with the default look). I was also able to leverage a set of high-quality typefaces available for download at no charge. The only downside is that the software was (and presumably still is) somewhat fragile, being based on an older version of Jekyll and various node.js modules, and requiring me to run an outdated version of Ubuntu.

The cover art proved to be a harder challenge. I had early on decided that I was not going to use any of Takako Shimura’s art either within the book itself or on the cover. I thought it would be difficult to impossible to get official permission to use it, and I didn’t want to risk a copyright dispute if I didn’t have such permission.

As a result I went looking for Creative Commons-licensed or public domain art that I could use for a cover. I went through at least three different cover designs (all featuring blue flowers of one sort or another) before concluding that none of them worked for me. I finally went to a commercial service (iStock, by Getty Images) and found a very nice piece of art that I could license for commercial use at a very reasonable price ($12). (The fact that it was a watercolor illustration was an unexpected bonus, since Shimura herself typically uses watercolor art in her own book covers.)

I used Pixelmator Pro to create the cover art itself, including the back cover, which I needed for the print version. The one major issue I had was with handling the colors for the print copy. My first attempt looked like crap when I had a proof copy printed, so I spent some time reading about CMYK colors (used for printing) vs. RGB colors (for online use), and ended up renting a copy of Adobe Photoshop for a couple of months in order to do the needed color corrections and conversions.

Between the book files themselves (PDF and EPUB3) and the cover art, I had almost everything I needed to publish. I decided to take the extra step of paying for ISBN numbers for myself, so that I could publish the book on platforms other than Amazon. (Amazon will assign you a so-called ASIN, but it’s usable only for Amazon itself.) I used Amazon Kindle Direct Publishing to publish the Kindle and paperback versions, and the Draft2Digital service to get distribution of the ebook version on all other platforms (Apple Books, B&N, Kobo, etc.)

The good: The PDF version of the book came out looking well in terms of cover art, typography, and general formatting, and the quality of the print-on-demand paperbacks produced by Amazon was pretty high—not a whole lot of difference from a typical trade paperback. The bad: I’d probably do it again just on general principle (to oppose the Amazon monopoly), but realistically there wasn’t much point to publishing on non-Amazon online bookstores; I think I sold maybe one copy on those platforms over the entire year.

The Japanese translation

A truly unexpected bonus of publishing the book under a Creative Commons license was having a pseudonymous blogger, Konsuke (a Japanese scientist working in the US), translate the entire thing into Japanese. A fan of Takako Shimura, he saw a tweet from Shimura mentioning the book (after I sent her a complimentary copy), took advantage of the book’s Creative Commons license, and started publishing translated chapters from the book on his blog.

I should state for the record how amazing and gratifying this was to me. Konsuke’s English was reasonably but not perfectly fluent (though he’s been actively working to improve it), and no one has yet read the translation and given me an opinion on its quality. But even a low-cost commercial translation of a nonfiction book of this size (about eighty thousand words) would have cost several thousand dollars.

In addition, Konsuke also found a number of typographical errors that remained after my own editing, discovered a number of places where the English translation of the manga was debatable or outright incorrect, created a new appendix listing the probable sources of all the chapter titles in the manga, and helped me learn about Japanese typefaces and typesetting practices, all of which improved the final editions in both languages.

The good: I have a complete Japanese translation, available in the same format and from the same sources as the English translation, and a significantly improved English edition as a side effect. The bad: I haven’t gotten any feedback on the quality of the translation from someone truly fluent in both languages.

If you want to write a book

Writing That Type of Girl took a lot of time (two or three years), a lot of work (probably at least a couple of hundred hours total, if not more) and a fair amount of money (probably around a thousand dollars all told). But I’m very glad to have done it: it was a great experience, I learned a lot about Sweet Blue Flowers, Japanese society and history (especially with regard to LGBTQ+ issues), and book production, and I even got a few readers as well.

So if you’re thinking that you have a book in you, I encourage you to let it out. You can save a lot of the money I spent by using only FOSS software (like Bookdown) or using a self-publishing site that is free or low-cost. If you want to make the book available for sale as a paperback or ebook, I recommend sticking to Amazon, monopoly though it may be. And if you want to encourage other people to translate or other build on the book, I suggest that you release the book under a Creative Commons license, and make the underlying text source publicly available. Giving away the book or its source for free will not harm any book sales, which will likely be approximately zero in any case.

A final thought: If you’ve read my book and have thoughts about it, good or bad, please feel free to email me or leave a comment. Positive feedback is always gratifying, and constructive criticism about how the book could be improved is always welcome.

Renkon (@renkotsuban) - 2023-03-15 12:08

This was a super enlightening read on self-publishing, thank you so much for sharing!

Frank Hecker (@hecker) - 2023-03-15 12:51

You’re welcome. Thanks for stopping by!

Mightfo (@Mightfo) - 2023-03-15 10:59

Thanks for sharing all this! I hadnt thought of using source control for books but thats probably something id want too, heh. Really interesting to hear about Konsuke and also the paperback color issue.

Frank Hecker (@hecker) - 2023-03-15 12:55

Yeah, using git for this was invaluable, even if no one else ever uses the repository. Konsuke and I went through a lot of revisions on the translations, where he would send me stuff to change. I’d then file an issue, create a branch, make the change, merge it back, then send him a copy of the diffs to confirm that the change had been made correctly. Since the book was first published I filed almost a hundred issues for stuff like this, both for the Japanese and the English editions.