[This post and its associated comments were originally published on Cohost.]

A few weeks ago I watched the 2020 film Minari, about the struggles of a Korean-American family that moves to rural Arkansas in the hope (at least, the father’s hope) of starting a farm to grow vegetables for a growing US population of Korean immigrants. The area where I live is home to a large Korean-American population so I had an inherent interest in the film, and it’s also been very well-reviewed.

In short, I saw the film, I really liked the film, and (as I often do) I wanted to read more about the film. The most interesting tidbit I found was that Lee Isaac Chung, the writer and director of Minari, was inspired to make the film by reading the 1918 novel My Ántonia (accent on the first syllable, please) by Willa Cather, a novel with a setting and plot that reminded Chung of his own childhood growing up on a farm in Arkansas.

I’d always meant to read something by Willa Cather, so I decided to remedy my lack by downloading a (public domain) copy of My Ántonia. I’m out of practice reading fiction, but I couldn’t stop reading the novel once I started it; I highly recommend it as well. And, as I also often do, I have thoughts (with minor spoilers for the film and novel) . . . .

The othered

Let’s start with the most notable controversy about Minari, the (universally ridiculed) decision to exclude it from consideration as a Golden Globes “Best Picture” nominee on the grounds that most of the dialogue was in Korean. In an interesting article on the film, subtitled “Why Do We Still See [Minari] As Foreign,” Alyssa Songsiridej claims that we don’t see My Ántonia as an “immigrant story” because “[Cather] writes about European immigrants, who are not othered in American culture.”

With all due respect, I think this is a misplaced criticism. First, if My Ántonia were in fact made into a film (as Chung initially thought of doing), a faithful adaptation would have much of the dialogue be in Czech—the titular Ántonia having migrated as a child from Bohemia, in the modern-day Czech Republic. Since it’s a novel, not a film, we miss the immediate experience of actually hearing the Czech language—or, for that matter, the Swedish, Norwegian, and Russian (or is it Ukrainian?) spoken by other characters in the novel.

Second, European immigrants were very much “othered” by the dominant American culture at the time; this is reflected in the novel, as Songsiridej acknowledges: “My Ántonia is actually considerably more concerned with xenophobia and culture clash than Minari.” “Othering” new immigrants is a consistent theme in American history from before the Revolution. To give but one example, Benjamin Franklin complained about German immigrants, asking “why should the Palatine boors [Germans] be suffered to swarm into our Settlements” and speculating that they “will never adopt our Language or Customs, any more than they can acquire our Complexion.”1

As Songsiridej also notes, in Cather’s novel “[Ántonia] and the other foreign-born ‘hired girls’ are viewed as exotic [and] potentially dangerous.” (To be more specific, the danger is presented as specifically sexual—that the “exotic” immigrant girls would seduce native-born men.) Remember, we’re talking about Swedes and Norwegians here, people who (along with Germans) present-day white supremacists would hail as being of true “Aryan” stock. But, again, Franklin in particular did not include Swedes or Germans—or, for that matter, the French, Spaniards, Italians, or Russians—among “the Number of purely white People in the World.”

Men, women, and children

Another interesting point of comparison between Minari and My Ántonia is in gender roles. Minari is based on Lee Isaac Chung’s memories of his own family, with the character of the young boy David in the film modeled on himself, and David’s father Jacob based on Chung’s father.2 In the film, Jacob is portrayed as motivated by a desire to provide for his family and build a better life for them, and Jacob passes this lesson down to David. In contrast David’s sister Anne is relatively undeveloped as a character, as is her relationship with her mother Monica.

In My Ántonia, on the other hand, women are very much at the forefront. The book’s narrator, Jim Burden, a young boy who moves to Nebraska at the age of 9 and meets 12-year-old Ántonia, is clearly a stand-in for Cather.3 Ántonia herself is based on Annie Sadilek, who was three years or so older than Cather, and who immigrated to the US at the same time Cather’s family moved from Virginia to Nebraska. I defy anyone to doubt that Cather was a lesbian after reading My Ántonia: much of the novel reads as a love letter from Jim/Willa to Ántonia/Annie.

The women of My Antonia almost leap from the page in their vitality, in particular Lena Lingard, the daughter of Norwegian immigrants who dominates the central section of the book. Some of the women get married, settle down, and have children. Others remain single and independent, making a living in fields as disparate as dressmaking and gold mining.

Politics and patriotism

A third aspect of both Minari and My Ántonia that I find interesting is their political stances—or rather, their apparent lack of them. As noted above, Minari is relatively silent regarding any difficulties caused by discrimination against Korean immigrants; the conflict and drama in the film are instead driven by the difficulty of farming and the growing estrangement between Jacob and Monica. It is similarly silent on the fact that Jacob and Monica would have been prohibited from immigrating to the US less than twenty years before the time of the film, and only briefly alludes to the political situation in South Korea that presumably led them to emigrate.4

My Ántonia is set in a time just after the conclusion of the main events of the “Indian Wars” (including the Battle of the Little Big Horn in 1876), and just before the rise of the populist movement in the Great Plains, which would culminate in the 1896 Presidential campaign of Nebraska congressman William Jennings Bryan. However, these events go almost totally unremarked in Cather’s novel.

I suspect that this lack of historical and political context is in large part because the primary events of both My Ántonia and Minari are viewed through a child’s eyes, explicitly so in the former and implicitly so in the latter—although My Ántonia extends through the college years of its narrator, and concludes with a final scene of him as an adult. To a child the world consists of their immediate family and environs, and events from afar and from before their birth affect them only if they impact that small world in which they live.

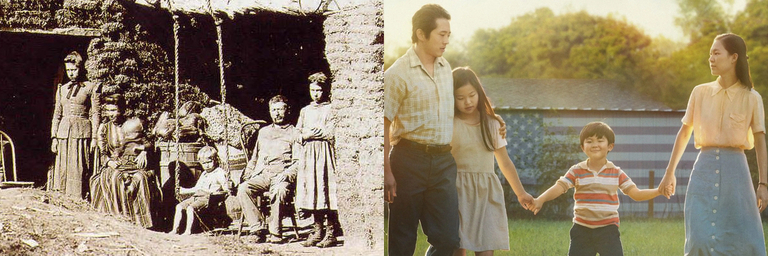

A final aspect of both Minari and My Ántonia is an understated patriotism that runs through both the film and the novel. (The imagery of the American flag in the Minari publicity shot above is not characteristic of the film itself; I suspect it may have been created to help convince audiences that, yes, this is really a movie about Americans.)

That patriotism I would characterize as a “patriotism of the land.” The land of My Ántonia and Minari is the site of past conflict (both between indigenous peoples and between those peoples and the newly-arrived settlers5), present beauty (gloriously depicted in the scenes of the film and the descriptions of the novel), and future possibilities.

Ethno-nationalists and white supremacists sneer at the idea of “magic dirt” with the power to convert non-Anglo immigrants into full-fledged Americans after they arrive on US soil. Yet in a way that is exactly what happens in both Minari and My Ántonia: the struggles of families to survive tie them more tightly to the land that they farm and the country of which it is part, a country they see as giving them new opportunities to make a better life for themselves and their children. The novel and the film were created almost a century apart, but in their essence are both very “American” stories, in the best sense of that term.

Mightfo (@Mightfo) - 2023-05-17 10:43

Its fascinating hearing that remark fron Franklin- i was very aware of various groups like the irish not being considered white, but wasnt aware how narrow the perception of that was a mere 100 years prior. I feel like reactionary bullshit ideas always get more ridiculous and incoherent the further back you go, and their modern versions trotted out by conservatives, fascists, etc are essentially repeatedly cleaned up and rationalized versions of even more insane nonsense from the past, yet paired with posturing about coherent consistent tradition.

Its really cool that the women in Antonia are depicted in such a varied and strong way, for a novel that old. I know feminism was active then, but still.

With the criticism of the Golden Globes, i feel like your counterpoint partially falls flat because theres a difference between “whos othered now” vs “whos othered back then”. The point about medium seems relevant though.

I feel like theres a lot more to that notion about struggles and ties to the land/culture/etc - fundamental psychological and sociological and human things, but not able to articulate those loose notions right now..

Also, Its nice to see you post again!

Lastly, did you happen to read my recent longer posts - one about gnc people and the one about ww2? Would love to hear any thoughts you have on those, including what was the least known part about the former or if a particular mention in the latter struck you.

Frank Hecker (@hecker) - 2023-05-17 17:30

Thanks for your comment! I always love hearing your thoughts. A couple quick comments in return:

On “othering”, maybe I didn’t express it well, but I guess my point was/is that today we don’t consider the story of My Ántonia to be “foreign” to us, but I’m not sure that would have been the case in 1918. After all, that was a time of very strong anti-immigrant sentiment, directed not only at Asian immigrants but also against those from Eastern Europe. So I was really making the analogy Minari : audience of 2021 :: My Ántonia : audience of 1918 in terms of their respective receptions. (But, really, before commenting further I should go back and see what sort of reception My Ántonia actually had from readers and reviewers in 1918. I may be totally wrong in what I wrote there and here.)

On the GNC post, I thought it was quite interesting, but as a non-GNC person myself I felt uncomfortable commenting on it. But I’ll go back and read both it and the WW2 post again and see if I have anything useful/interesting to add.

Mightfo (@Mightfo) - 2023-05-17 17:47

Well, the criticism seemed to be about both Minaria and Antonia(and other stories about european immigrants) today, not about each in their release time. Maybe im misunderstanding something about us talking past each other, but perhaps a more relevant phrasing may be “why are stories about asian immigrants still ‘foreign’ while stories about later european immigrants have ceased to be foreign?” The timing analogy is generally useful, but I dont think its a rebuttal to the current-time-focused point in the article about the golden globes.

Im glad the GNC post was quite interesting! I understand feeling uncomfortable commenting on that for that type of reason, although I am curious as to the degree of knowledge/understanding people are at before they read articles like that(and theres nothing wrong or offensive with simply not knowing/understanding of course). When you see a varied series of somewhat infrequent misconceptions and then try to clarify a general set of things to counter that, it can be hard to know what’s actually new information to an average reader, including in various subaudiences of the readership. But if also you dont really have anything to say, thats fine too ofc.~

A personal note here: My family hails from the area around Cincinnati, Ohio, which supported multiple German-language newspapers, with a total readership of over 100,000, until the US entered World War I (at which point they were suppressed). My grandmother probably spoke German at home until her teen years. ↩︎

The biblical names are a tell: “Isaac” and “David.” ↩︎

The first edition of My Ántonia has an awkward preface that presents the events of the novel as being told to the author (i.e., Cather) by Jim Burden as an adult. Cather’s editor wisely advised Cather to drop it when the novel was reissued in 1926, and I recommend that you skip it if it happens to be in the copy you read. ↩︎

Minari takes place in 1983, with Jacob and Monica having immigrated to the US at least ten years before, during the authoritarian regime of Park Chung Hee. US restrictions on immigration from East and South Asia were lifted in 1965. ↩︎

The next-to-last battle on Nebraskan soil (in 1873) was fought between the Pawnee and the Sioux, and ended in the massacre of over 150 Pawnees. In the last battle (in 1876) “Buffalo Bill” Cody killed and scalped a Cheyenne warrior, and then went on to reenact the killing and exhibit the scalp in his “Wild West” shows. ↩︎