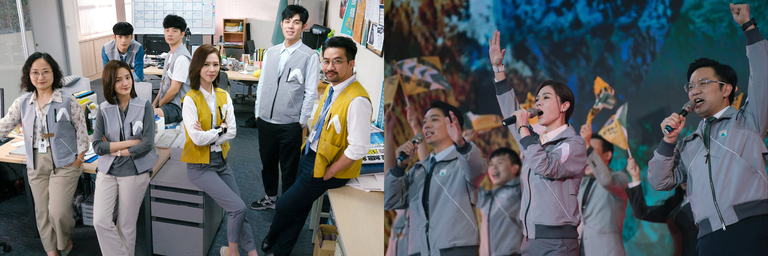

Left: The campaign team for the (fictional) Justice Party in the Taiwanese political drama Wave Makers, including Chang Ya-ching (second from left, seated, in a gray vest), Weng Wen-fang (center, in a tan vest), and Chen Chia-ching (right, in a tan vest). Right: Wang Wen-fang pumps up the crowd at a Justice Party political rally. Click for a higher-resolution version. Image © 2023 Netflix.

[This post and its associated comments were originally published on Cohost. Given the ongoing discourse about China and Taiwan, I thought it was worth publishing it on my own site. I’m a total newbie when it comes to China, Taiwan, and international relations, so consider this as published for amusement purposes only.]

A while back I commented on what I thought was a deliberate Taiwan government strategy to build “soft power” by funding films and TV series highlighting LGBTQ stories. Now comes an even more explicitly political TV series out of Taiwan, one that was publicly endorsed by Taiwan’s president Tsai Ing-wen.

Wave Makers is an eight-episode Netflix series focusing on the press and PR team (the “wave makers” of the title) working on a (fictional) Taiwanese presidential campaign. In a way it’s a Taiwanese equivalent of US shows like The West Wing and House of Cards, and like those shows is slanted and unrealistic in various ways both large and small. However, unlike the US, Taiwan faces an existential threat, and that makes Wave Makers more interesting—and more vital—than any US political drama might be. What follows is my (mostly) spoiler-free analysis of the show and its significance.

The players and the game

The story of Wave Makers features multiple generations and diversity in genders. The central character is Weng Wen-fang, a lesbian whose previous run for office ended in failure, and who now serves as the chief spokesperson for the (fictional) Justice Party. Her boss is Chen Chia-ching, whose long hours running the campaign threaten to estrange him from his wife and child.

Weng and Chen work in support of the presidential run of Lin Yueh-chen, who tries to balance her personal convictions with political expediency. Opposing her is the incumbent president of the (also fictional) Democracy and Peace Party, along with her newly-selected running mate Chao Chang-tse, who enlists his wife and daughter to help him present the image of a perfect political family.

Finally, the rising generation is represented by Chang Ya-ching, an aide to Weng whose past and present actions put her at the center of the evolving plot; Chao Jung-chih, the daughter of Chao Chang-tse, who comes to doubt her father’s integrity; and Tsai Yi-an and his fellow Justice Party campaign workers, who struggle to justify to their university friends their turn from student protests to conventional politics.

The series provides an idealized but informative look at what goes into running a political campaign in an always-online society, where even minor events (like a candidate being bitten by a supporter’s dog) require an “all hands on deck” effort by the PR team to keep the narrative from going in a unwanted direction. The Justice Party campaign team tries to find issues that will resonate with voters, criticizing the incumbent administration’s positions on the environment and playing up Lin’s support of new immigrants to Taiwan. However, as often happens in both fiction and real life, other issues get shoved off the stage as sex scandals both imagined and real seize the attention of the media and the general public.

All of that falls away, though, in the second half of the last episode: the campaign heads into its final days in a flurry of rallies and candidate appearances, election day arrives, and the various characters pause to cast their “sacred votes”—an act more significant in a society that only two generations ago was a one-party state under martial law—all ending in the counting of votes, the euphoria of the winners, and the despondency of the losers.

The existential question

For all of the political topics dramatized by Wave Makers, there is one that is not: the relationship between Taiwan and China. Creating a show directly addressing “cross-strait relations” from a Taiwanese perspective would no doubt put the kibosh on any hopes that Netflix might have of being allowed access to China, as well as risk derailing the careers of anyone in the cast or crew whose livelihoods are dependent on access to the Chinese market.

But this omission can also be viewed as a strength. In a review of the series, Chieh-Ting Yeh points out that “[the show] may actually be what the Taiwanese people prefer their politics to look like. . . . Rival politicians can debate immigration and environmental policies, fend off student protesters, and even dig up each others’ scandals without worrying about what anyone in Beijing or Washington says.” From this point of view, Wave Makers is a portrait of what Taiwan could be if it were not perpetually “amid tensions.”

But for those Chinese who are well-connected (in an Internet sense), and thus able to view the series via clandestine means, it can also be thought of as a vision of what China could be if it too were not “amid tensions” driven by the CCP and its leader. Based on reactions that have dribbled out, there are at least a few people in China who would prefer participating in a political system that offers real alternatives for the development of the country and its people, instead of spending their days being drilled on the fine points of “Xi Jinping Thought.”

In his essay “Politics,” Ralph Waldo Emerson quoted the early US politician Fisher Ames as saying that “a monarchy is a merchantman, which sails well, but will sometimes strike on a rock, and go to the bottom; whilst a republic is a raft, which would never sink, but then your feet are always in water.”1 Wave Makers is a portrait of life on that raft. Political parties may suffer reverses and losses, but (as a character says in one of the final scenes), “There’s always next time.”

On the other hand, in the last years of the twentieth century the Soviet Union struck on a rock and went to the bottom. The rulers of China are haunted by this event, which they ascribe to the growth of factions within the ruling party and the influence of “foreign” ideology. In a document produced for the indoctrination of party cadres, one can almost smell the fear that the ideological influence of “hostile forces” will lead to a “color revolution,” and that China (or, more correctly, the rule of the CCP) “will inevitably disintegrate like a sheet of loose sand.”

To preserve itself, the CCP must suppress not only actual opposition, but any ideas that might inspire such opposition: “Once the defensive line in thought has been breached it is difficult for other defensive lines to hold. In the realm of ideological conflict, we have no way to compromise and no place to retreat to. We must obtain total victory.” Thus the fear of “hot topics on the Internet” and the perceived need for the CCP to “increase the vigor of public opinion control.”

Thus also the importance to the CCP of “reunification”: beyond any historical justifications, expansionist ambitions, or desires to avenge the “century of humiliation,” the very existence of a democratic Taiwan is an existential threat to China’s rulers. Thus the increasing likelihood that China will move against Taiwan—if not through an actual invasion then through a “death by a thousand cuts” in which China incrementally destroys Taiwanese independence by means just short of outright war.

Thus, finally, two possible futures: one in which the ideas represented in Wave Makers inspire “counter-elites” within or without the CCP to exploit new waves of popular discontent and break the party’s monopoly on power, and one in which Wave Makers, like the films of pre-1997 Hong Kong, serves as a cinematic reminder of a democratic society that was, but is no more.

Mightfo (@Mightfo) - 2023-06-10 12:17

The comments from people in mainland China about that show are very interesting.

Bad governments rely on a constant battle against accountability and epistemology, increasingly resulting in brittleness and information closure that cripples their ability to respond to new situations, leading to self defeat. My impression is that the CCP has a higher degree of ability to respond to new situations with adjustments than, say, the USSR and certainly current Russia, but its difficult to ascertain exactly where they land since their system involves some technocratic and some semidemocratic components. Its easy to see that modern Russia is too brittle and irrational, guaranteeing failure, but one wonders how long governments with less extreme structural flaws can rule.

https://warontherocks.com/2023/05/xi-jinpings-worst-nightmare-a-potemkin-peoples-liberation-army/ Related, good article

maddie (@ninecoffees) - 2024-02-27 13:39

Thank you so much for writing this

Ames is sometimes misquoted as referring to “a democracy” rather than “a republic,” a mistake that would have annoyed him. A member of the Federalist Party, along with Washington, Adams, and Hamilton, he thought that democracy in its purest form would inevitably lead to despotism. ↩︎