[This post and its associated comments were originally published on Cohost.]

Before I found Cohost, I posted a fair amount to a pseudonymous 2-follower account on Twitter; a lot of my Cohost posts started out there. Here’s another one of these: some brief thoughts on the final scene in Alice Wu’s film The Half of It, thoughts originally inspired by a thread by lourdeslasala on symbolism in the film.

My bringing it up now was due to seeing a post by @MayaGay mentioning The Half of It in passing, along with Wu’s earlier film Saving Face, which I hadn’t seen. I quickly remedied that lack (Saving Face is streaming on Prime Video), and then watched The Half of It again on Netflix, because I dearly love the film and wanted to write about it again.

NOTE: The following contains spoilers for The Half of It, and assumes that you know the overall plot and who the main characters are.

In the penultimate scene of The Half of It (above), Ellie and Aster face each other, separated by a double yellow line. As lourdeslasala notes, it symbolizes the boundaries between the two, with Ellie staying in her “comfort zone,” but then breaking out of it to cross the line, talk to Aster, and then kiss her.

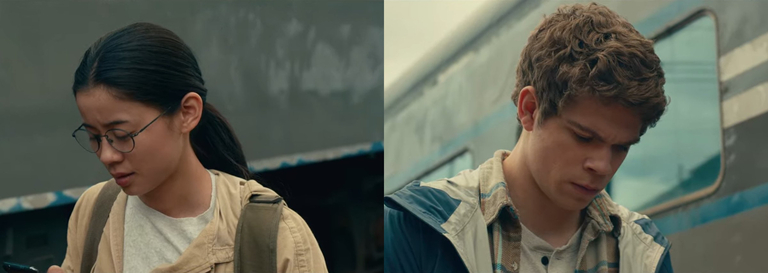

The final scene is between Ellie and Paul. It starts with another shot with a similar perspective, but a key difference. In the previous scene Ellie and Aster were situated similarly to each other, in positions of relative equality within the shot itself, and also in a wider context: Ellie going off to Grinnell College, and Aster looking to leave Squahamish and go to art school.

But in this shot there’s no such equality. On one side is the train that will take Ellie away to Grinnell. On the other is the town in which Paul will remain, probably for the rest of his life, working in and then presumably inheriting the family business.

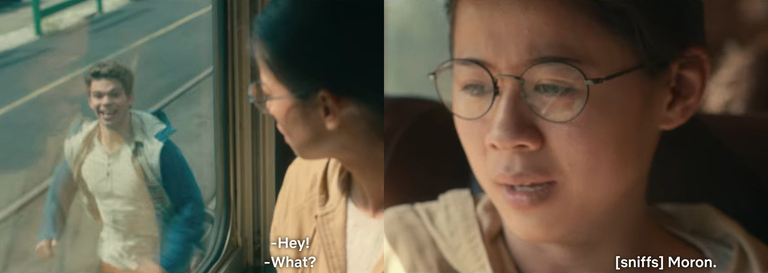

We next see Paul and Ellie’s parting conversation. Recall the earlier discussion between Paul and Ellie regarding “the look”: when you know someone wants to be kissed, and you should go ahead and kiss them—as indeed Ellie did to Aster in the previous scene. That was the third kiss in the film, and the only true one, the previous two having been given under false pretenses: Aster looking at Paul thinking that he was the person behind the letters Ellie wrote for him, and Ellie apparently looking at Paul but (it’s implied) looking past him at Aster.

But this scene is different. Here the look is not of two people who want to kiss, but two people who want to—need to—hug and be hugged. So why don’t they?

Because something is blocking them. That obstacle is literally a cooler, containing food prepared for Ellie’s journey. But as a metaphor it’s all the things that might act as barriers to Paul and Ellie’s friendship: interests and intellect, gender and sexuality, or even (as Alice Wu notes in an NPR interview) the jealousy of their partners, who might resent the level of intimacy Ellie and Paul have.

Or, at least, the intimacy they had. Here neither Ellie nor Paul can find the words they seem to want to say, and are blocked from the hugs they might want to give and receive. So, instead, Ellie resorts to sending Paul a text containing (only) emojis. It’s a harbinger of how their relationship may be in future: although they may meet again, they may never again experience the closeness they have right now, their future interactions mediated by distance and differing experiences, as it’s here mediated by technology.

But even in the face of all those barriers to their friendship, Paul can’t help chasing Ellie’s train, echoing a scene from the film Ek Villain that they had watched earlier—a scene that Ellie had scoffed at. Ellie again scoffs at the gesture, but she’s fighting back tears as she does. It’s a platonic parallel to the romantic moment between Ellie and Aster, and to my mind a perfect ending to a beautiful film. Or, as Ellie’s father would say as he pointed to his favorite movie scenes, “Best part.”

Ramona (@MayaGay) - 2023-06-09 18:50

Wonderful analysis!!

Frank Hecker (@hecker) - 2023-06-09 18:54

Thanks! I really liked Saving Face, but The Half of It holds a special place in my heart. I wish for more Alice Wu films…

Ramona (@MayaGay) - 2023-06-09 18:59

So do I, I think she is such a talent! Here is hoping she is given many more chances to show how much she can do.