[This post was originally published on Cohost. It was in response to another Cohost post by the user @things-to-read.]

Joanne McNeil comments about science fiction that “the prestige and mainstream acceptance arrived over the course of the past two decades . . . but at a cost, these new readers tend to straightjacket what’s interesting about the genre.” One symptom of that mainstream acceptance and respectability is the increasing number of science fiction authors whose work has been published in new editions by the Library of America, an organization self-described as “publishing America’s greatest writing.”

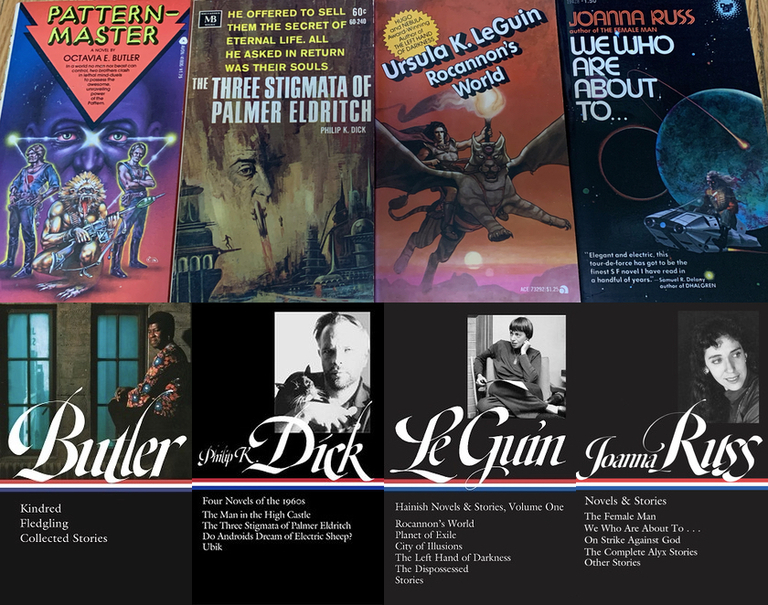

Such editions strive to make science fiction respectable partly by their cover design, which flattens the vast and wild corpus of American literature into a uniform package of restrained visual design. Note the contrast between the garish paperback originals shown above (from my own collection) and the same authors in Library of America livery.1

Let’s start with Philip K. Dick. Dick has been a Library of America darling, with three separate collections of his novels and short stories, many of which he wrote while hopped up on amphetamines, trying to earn enough money to feed himself and make his alimony payments. As McNeil notes,

[Dick] was a serious weirdo and very frequently hilarious (and, yes, problematic). . . . But to be legible to scholars and critics, they construct a character out of his legacy: a serious man, . . . the sort of person who could show up on NPR and tell us exactly what the world is like and where it’s going.

McNeil continues, “This is happening with Octavia Butler in real time. Her daring and the moral complexity of her characters is swept away in recent assessments to create a coherent legacy—that of an earth mother tote bag caricature-icon.” Have these people even read Butler’s works? There’s some seriously fucked-up shit going on in most if not all of them.

As McNeil notes, Ursula K. Le Guin has also been welcomed into the pantheon of American literary giants; she now has six Library of America books in print (and two more available as ebooks), twice as many as Dick. She went from writing Ace paperback originals to being lauded by uber-critic Harold Bloom and appearing on a US Post Office stamp.

Finally, we now have an upcoming Library of America edition of works by Joanna Russ, another writer who got her start writing Ace paperback originals. This one I’m glad to see, as Russ is one of my favorite writers; I have over two dozen books by her or about her. I recommend checking this one out if you’ve never read any of her work. (A content warning, though: The Female Man, the 1975 feminist novel that’s her most famous work, has a pretty TERF-y scene for which Russ later publicly apologized.)

Now that science fiction has achieved a measure of respectability, McNeil speculates (albeit with little evidence) that the romance genre is a place where one might find the Octavia Butlers and J.G. Ballards of the future: “It is the one genre left that has evaded mainstream acceptance. . . . Romance writers work outside traditional measures of literary prestige.”

Russ herself wrote a romance of sorts, On Strike Against God, one of the works included in the Library of America edition. It’s one of her lesser works, mainly of interest as a semi-autobiographical account of Russ’s coming out as a lesbian, and pretty much of a piece with any of the lesbian romances you might find in the “LGBT” section of your local independent bookstore.2

So, although Russ was a leading light in the science fiction “new wave” of the 1960s and 1970s, I can’t imagine her as part of McNeil’s speculative “romance lit avant-guard [sic].” Which prompts the question: now that science fiction has been (mostly) mainstreamed, is there anyone at all writing in today’s sneered-at-by-literati romance genre whose work exhibits the loopiness of Dick, the bizarreness of Butler, the humanity of Le Guin, or the fierce intelligence of Russ? Enquiring minds want to know.

Note that I had to cheat a bit in the case of Octavia Butler, since I don’t possess a paperback copy of Butler’s Kindred and the Library of America hasn’t published an edition of the novels in the Patternist series. Also, I left off Kurt Vonnegut, who apparently loathed the idea of being considered a science fiction writer, and who was lucky enough to escape that fate. ↩︎

SF and fantasy writer Nicola Griffith has suggested that it would have been better to replace it with more of Russ’s short stories, and I agree. ↩︎