What does it mean to be an American? Are some people inherently more “American” than others? And, if so, what if anything does that imply?

[UPDATE 2024-09-27: I revised the final paragraphs of the post and expanded them into a new section “clan and country,” after thinking about a point I had not previously considered.]

Although I’m a life-long registered Democrat and would be considered “liberal” by most or even “leftist” by some, I make it a regular practice to read people who have different political beliefs than myself and who have shown themselves to be more than mere ideologues and political strivers. One of those is Tanner Greer, the (relatively) young conservative intellectual who writes at The Scholars Stage; I’m subscribed to his Patreon and follow him on X (fka Twitter).

Thus when Greer gave a positive recommendation to an opinion piece by Joshua Treviño, “America as Place and People: Understanding J.D. Vance on history and nation,” I thought it worth checking out, and after reading it worth writing in response.

Treviño urges us to watch or read Vance’s speech to the Republican National Convention. I’m sorry, but I’ll take a pass on that. Political speeches are in their essences sales pitches, and having worked in sales groups most of my life I have no desire to watch or read sales pitches when I’m off work, even those that pander to my own political views. What really matters is the end product that the American people would end up buying, i.e., what actions Vance would support Donald Trump in taking were they to win office.

But Treviño’s piece is worth reading because it functions in the same way as, say, a Gartner report does in the industry space I work in: it seeks to provide some intellectual substance behind the sales pitch and to bend the mind of the “prospect” in a certain direction, to think of the problems at hand in one way (one favorable to Vance, Trump, and others) rather than another.

Not a “propositional nation”

So, what is Treviño’s “pitch behind the pitch,” as it were? He takes as his starting point a quote from Vance’s speech, the core of which is this: “America is not just an idea. It is a group of people with a shared history and a common future.” Treviño then contrasts that with “propositionalism,” that the essence of the U.S. is in certain ideas—e.g., “all men are created equal,” “government of the people, by the people, for the people,” etc.—that exist independent of ancestry and ethnicity and could in principle be adopted by anyone and take root anywhere.

In Treviño’s view, prepositionalism “eradicated the enduring Western understanding of what a nation or a polity actually is,” goes against “millennia of tradition and political thought,” and has various ill consequences, most notably including the acceptance of high levels of illegal immigration and the “demand that the deeply rooted peoples of the land adapt themselves to the newcomers, but never vice versa.”

Treviño’s position is rather that America arose in a particular historical context: “the Christianization of England, the Protestant Reformation, the Elizabethan settlement, the English Civil War, King Philip’s War, the Glorious Revolution, Locke, and so on.” That in turn implies that although it is certainly possible for anyone to become an American, some Americans are more closely associated with that historical context than others, and are thus “more-normatively American, and more fully constitutive of America” than others. Therefore “the community and the history that made the America to which the immigrants arrive is the standard—and deserves a positive defense.”

Treviño protests against those who would immediately leap to interpret this argument as justifying bigotry and anti-immigrant sentiment. So rather than jumping directly to evaluating the good and bad in this line of argument, and arguing points in opposition to it, I’d rather start by talking about mathematics.

A mathematical immigrant

Although mathematics is often thought to exist independently of mathematicians themselves, in fact modern mathematics as we know it (from the Renaissance on) arose in a particular historical context and in a particular set of Western European nations. Whether it could have arisen elsewhere in the same form is an open question, but in practice it did not.

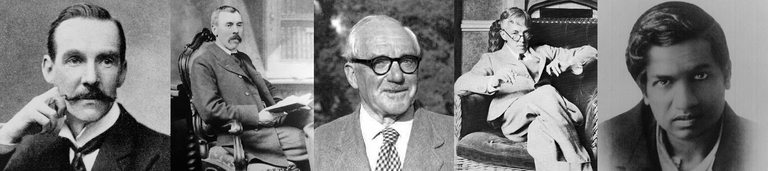

That history privileged not only surface aspects like mathematical notation but also particular ways of doing mathematics and beliefs about which mathematical questions were considered most important. That history also manifested itself not only in distinct national differences (it was in no way an oxymoron to speak of “French mathematics” versus “German mathematics”) but also in families in which multiple generations were mathematicians. Where no actual family ties existed, mathematicans constructed fictive families of a sort, in which one mathematician taught others who then went on to teach others still, so that each mathematician could look backward to their own line of mathematical “ancestors.”

Therefore, “as a purely objective matter” it would be true that (say) a third-generation Bernoulli would be more “more-normatively [a mathematician], and more fully constitutive of [mathematics]” than (say) a poor Indian of humble origins working as an accounting clerk. Then the question might arise, what should be done if such a person were to come knocking at the door of European mathematics asking to be let in?

Those familiar with the history of mathematics will recognize this as the story of Srinivasa Ramunajan, a prodigy who sought to bring his work to the attention of mathematicians in England. Some shut the door against him, including E. W. Hobson and H. F. Baker, but eventually J. E. Littlewood and G. H. Hardy let him in, to their ultimate benefit.

But this was not a one-way affair. While receiving the fruits of Ramanujan’s genius, at the same time Hardy and Littlewood indoctrinated him in the “norms” of European mathematics, including in particular what constituted a valid proof of a result and what did not. They were not always successful in this, but they made the effort and considered it important to do so, because “the community and the history” that made the European mathematical tradition was “the standard.” For those rooted in that tradition and Ramanujan to mutually benefit from their interactions, Ramanujan needed to adapt to the ways of the tradition’s “natives” as much or more than they needed to adapt to Ramanujan.

Immigration policy as if assimilation mattered

Coming back from European mathematics to American politics, we can immediately derive some reasonable implications for immigration policy:

First, that some sort of gatekeeping is necessary, but it should be combined with openness to those who seek to come and could enrich the native tradition. Hobson and Baker were not wrong to dismiss someone who could well have been simply a mathematical crank, but at the same time it was and is a blessing to mathematics that Hardy and Littlewood were willing to take a chance on Ramanujan.

Second, as Anton Ego might have said, not everyone can be a good American, but a good American can come from anywhere. Thus immigration policy and indeed American society at large should self-consciously select for immigrants who would make good Americans, not by ethnicity or country of origin but based on more personal characteristics: their willingness to abandon “clannishness“ in favor of a law-based liberal order, personalities that put them in the higher percentiles of traits we associate with stereotypical Americans, and a level of relaxed tolerance sufficient to enable them to coexist with their neighbors wherever their American journey might take them, whether that be New York City, Salt Lake City, or somewhere that’s not a city at all.1

This selection process could occur either before or after immigrants arrive. There is nothing wrong with encouraging certain types of people to immigrate as opposed to others. And if an immigrant is not willing or able to conform to American social norms, there’s nothing wrong with encouraging them to voluntarily return to their home country, and assisting them in so doing. But if they like America and fit in to American society, then we should endeavor to give them a sure and certain path to full citizenship.

Immigration policy in the time of Trump

However, having floated an alternative vision for immigration policy, I presume that the chances of anything like this being implemented are slim to none, given the need for at least partial GOP buy-in. Attempts to find a bipartisan consensus on border security appear to have been blocked by Donald Trump’s decision—and Mike Johnson’s acquiescence in that decision—to inflict upon the nation several more months of “chaos at the border” in the hopes that it would improve his election chances.

Then there’s the proposal to keep non-citizens from voting, presumably while continuing to count them for purposes of Congressional reapportionment, thus depriving one group of political power in order to increase the political power of others. It’s a strategy not unknown in American history, here more effective because it would count the disenfranchised at their full numbers rather than at just a fraction.

As for the possibility that the Republican party might find a more nuanced approach to immigration policy based on a rejection of propositionalism and the valoration of a “shared history and common future,” in the end I don’t think it matters what Treviño thinks, or even what J. D. Vance thinks. As Tanner Greer points out in another article (riffing off Jo Freeman), the Republican party is controlled by whoever happens to be its leader, and right now that leader is Donald Trump. Vance will adapt to Trumpism (indeed he already has) and not vice versa. And thus Vance’s wife Usha, whose parents arrived here from India, got to make her speech at the Republican national convention confronted by a sea of RNC-printed and -distributed signs reading (in all caps) “mass deportation now.”

If not a “propositional nation,” then what?

If America is not to be a “propositional nation,” what are the alternatives?

One possible left-wing response is to view those propositions as nothing more than empty promises, and the history of the US as nothing more than a history of genocide, oppression, and imperialism. One possible right-wing response is to reimagine America as an ethnostate in which all Americans are “real,” but some are more “real” than others.2 We’d then have to go to Ancestry.com to see who trumps whom.

Both these responses are lacking. The left-wing response leads some to excuse similar or worse genocide, oppression, and imperialism as practiced by foreign dictators, as long as those dictators present themselves as anti-American. The right-wing response puts new Americans in a permanently inferior position relative to the “natives,” like people who move to an insular small town, live there for most of their lives, and still are regarded as “newcomers” not truly accepted into small town society.

Moreover, both these responses devalue what it means to be an American, and destroy that sense of American exceptionalism on which we have always prided ourselves. If America is just an ethnostate, with an in-group of “natives” and an out-group of “others,” what distinguishes America from China, Japan, Korea (North or South), or any other country organized around blood, not beliefs?

And why would Silvestre Herrera, the Medal of Honor winner lauded by Treviño, have charged so boldly into a hail of machine gun fire if he did not believe that America was as much in him, and he in America, as anyone who could boast of “a six-generation lineage on the western-Appalachian slope”? As Abraham Lincoln said regarding Blacks enlisting in the Union Army, “Why should they do any thing for us, if we will do nothing for them? If they stake their lives for us, they must be prompted by the strongest motive.” Some may dismiss the propositions with which America was birthed and preserved, and others sneer at the “magic dirt” that supposedly can turn Them into Us. But the promise that all men are created equal, and the extension of that promise to those formerly excluded from it, have proved to be among the strongest motives of all.

What makes a nation

If not blood, what makes a nation a nation, and its citizens members of it? Shared life experiences both small (e.g., typical school life) and large (e.g., wars, political, social, and economic upheavals, etc.). In-group markers like language and accent, religion, style of dress, food preferences, and so on. Particular personality traits treated as desired national norms. And last but not least, acceptance of a particular national narrative (“stories nations tell themselves”) and one’s participation in it.

New immigrants lack the first two, but they can certainly act like Americans, and they can accept and take part in the story of America, so that the problems of America become their problems to deal with, and the triumphs of America victories in which they can take pride. Those born to immigrants in the US, or who have come to the US as young children, have all four: they have shared their life experiences in school, play, and elsewhere with their peers, and from their peers they have acquired accents, tastes, and attitudes similar or identical to those of other Americans their own age. And of course they have literally been schooled in American history and the propositions associated with it. It is an insult to them to look at, say, a picture of American winners of an international mathematics competition and (as one person did on X) refer to them as “Team China USA.” They are Team USA, period.

Clan and country

However, perhaps I’m doing Treviño an injustice. Let’s look more closely at his argument as it might apply to Treviño’s own Chinese-born son, who “bears the name and the inheritance of one of the original Americans.” If one were a true ethnonationalist then Treviño’s statement would seem to make no sense: Presuming his son was adopted, how could he be the rightful heir to “the name and the inheritance of one of the original Americans”? A true ethnonationalist could and presumably would argue that Treviño’s son has no right to that name, that his bearing it is simply a form of “stolen valor.” By those lights his true inheritance is instead that of the Wangs and the Zhangs.

How to reconcile this? One way, and perhaps the way that Treviño intended, is to consider lineage not as determined (solely) by genetic descent, but (also) by the transmission of culture from parents to children, who then pass it down to their children in turn, and so on down through time. The deeds of ancestors are honored by their descendants, and their precepts instruct and inspire them.

From this point of view, what matters is not the circumstances of Treviño’s son’s birth but the consequences of his upbringing: By growing up in a family that can trace its roots (biological and cultural alike) to the earliest days of America, he is now considered a full member of that family—a social fact, if not a biological one. As such he can presumably be considered “more-normatively American, and more fully constitutive of America” than, say, a hypothetical twin brother who was born at the same time and place, and arrived in America at the same time, but who grew up within their own (Chinese immigrant) family.

This is certainly a more palatable argument than one that relies solely on ethnicity as the mark of a “real American.” There are also positive aspects to emphasizing the importance of families and their traditions. But I still have a problem with the idea of elevating Treviño’s son over his hypothetical non-adopted twin when it comes to measuring “American-ness,” when both grew up in the same American cultural milieu and would both almost certainly appear equally “American” to those ignorant of their different family situations.

I also think this argument risks returning us at least partially to the days when one’s membership in and loyalty to one’s extended family—in other words, one’s clan—was considered far more important than one’s membership in and loyalty to the nation of which one’s clan was a part. We spent several hundred years liberating ourselves from the “rule of the clan,” and I for one do not wish to go back to it.

I would much rather echo the sentiment of the man who quoted this letter from a constituent:

Since this is the last speech that I will give as President, I think it’s fitting to leave one final thought, an observation about a country which I love. It was stated best in a letter I received not long ago. A man wrote me and said: “You can go to live in France, but you cannot become a Frenchman. You can go to live in Germany or Turkey or Japan, but you cannot become a German, a Turk, or a Japanese. But anyone, from any corner of the Earth, can come to live in America and become an American.”