The Decline of S

As mentioned in the introduction, Sweet Blue Flowers can be seen as both homage to and critique of the early twentieth-century Class S genre. What was the process by which a manga created in the early twenty-first century would ring changes on short stories and novels written almost a century before? In other words, how did we get from Class S to the genre we now know as yuri?

I do not have the time, space, or expertise to present a complete “history of yuri.” Erica Friedman has provided both a concise introduction1 and a more comprehensive history.2 Verena Maser’s doctoral dissertation is the most in-depth academic treatment.3

My interest is in two specific questions. This chapter discusses the first one: why did Class S culture and literature decline (pretty much to extinction) after World War II? (The next chapter discusses the re-emergence of Class S tropes near the end of the twentieth century.)

That Class S culture and literature did suffer a precipitous decline in the postwar period is evident. Although publishers attempted to revive them after the war, the magazines that previously carried Class S stories and formed a nexus for Class S culture either shut down or shifted their focus.4

Recall the hypothesis in a previous chapter that the popularity of S relationships, and Class S literature depicting such relationships, was a function of the lack of choices open to Japanese schoolgirls: for girls destined for marriages arranged by their families, S relationships were an area in which the girls could freely choose their partners and enact rituals of courtship related to those choices.

Suppose that this hypothesis is true to at least some degree. If that is the case, a hypothesis for the postwar decline of S relationships and literature immediately suggests itself: that the nature of relationships between girls and boys and women and men changed significantly under the postwar American occupation, and that these changes taken together destroyed the social context within which S relationships had originally flourished.5

The first such change was public schools (and some private) moving to a coeducational model in which girls and boys attended the same schools and received equivalent elementary and secondary educations. Before the war, girls were educated separately from boys and received fewer years of schooling. Under the occupation, the American authorities encouraged the adoption of coeducation, apparently in part due to the concerns of American women staff members that this was the only way to ensure that girls received an equivalent education to boys.6

The second change was in Japanese attitudes and behaviors relating to relationships between men and women, particularly dating and courtship. Beginning in the Meiji era, the Japanese government attempted to exert stricter control over family life, with women expected to serve (only) as wives and (especially) mothers, and men expected to remain monogamous—albeit with the freedom to engage in sex outside of marriage.

The government redoubled these efforts in the Shōwa era after Japan invaded Manchuria in 1931, with “women being cast as mothers whose sole purpose was to breed sons for the empire, and men being regarded as fighting machines.” Particular measures included a National Eugenic Law, prohibition of abortions, and restrictions on contraceptives (including censorship of discussions of the use of condoms for family planning as opposed to disease prevention).7

After World War II ended in Japan’s defeat, many people in Japan were presumably sick of these wartime restrictions. As it happened, the American occupation authority had an explicit goal of promoting American cultural norms around love, courtship, and marriage, up to and including encouraging Japanese moviemakers to include scenes of kissing in their movies.8 The result was not a wholesale repudiation of traditional Japanese social norms, but it did mark a fairly decisive change from prewar behaviors.

Taken together, coeducation and the rise of American-influenced dating and courtship behaviors eventually led to the (effective) end of arranged marriages, at least as an unquestioned cultural norm. This change can be seen quantitatively in statistics published by the Japanese government and qualitatively in the postwar “home dramas” of director Yasujirō Ozu, which were made for a middle-class audience and reflected middle-class concerns and aspirations.

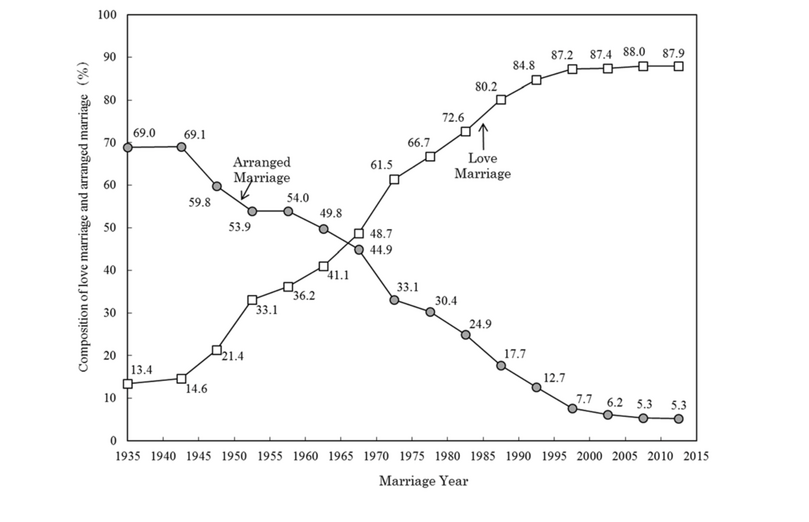

The quantitative data are from the 2015 “Fifteenth Japanese National Fertility Survey” conducted by the Japanese government.9 The survey queried respondents about the years in which they got married and how they happened to have met their spouse. It defined arranged marriages as marriages occurring “through an arranged introduction” or “through a marriage match-making agency.” The survey defined love marriages as marriages in which the couple met in other ways, for example, at school, at work, through friends or family, or while pursuing a hobby.10

The graph included in the survey report features a classic S-curve showing the rise of love marriages from a low base to almost complete saturation in the population, with an early high-growth phase from World War II through the late 1960s. The decline of arranged marriages is visible in a corresponding S-curve, with the percentage of arranged marriages dropping below 50 percent around 1960 and ending up in single digits by the late 1990s.

We can match points on the curve to Ozu films made over the course of a decade. First is the 1949 film Late Spring, the first film in the so-called “Noriko trilogy,” featuring (unrelated) characters named Noriko.11 In the late 1940s, arranged marriages were still the dominant norm, and love marriages were the province of a small minority. Thus it’s no surprise that the first Noriko feels she has no choice but to defer to her father and marry a man suggested to her by her aunt.

Censorship prevented Ozu from explicitly presenting this as an arranged marriage but it has the look of one, and Noriko does not want to enter into it.12 However, there is also a glimpse of the new dispensation: earlier in the film Noriko accompanies her father’s assistant on a date of sorts, as they ride their bicycles to the seashore.13

Almost ten years later, love marriages were over a third of all marriages and still rising in popularity. In the 1958 film Equinox Flower, Fumiko explicitly rebels against an arranged marriage in favor of a love marriage with a musician, while Setsuko tries to persuade her father to permit her own love match with a salaryman. Setsuko’s father approves of love marriages in theory (in response to a question posed by her friend Yukiko) but not for Setsuko. However, he finally relents and gives his blessing to the happy couple. Fumiko’s father does likewise, and we see a new custom well on its way to becoming pervasive.14

Consider a Japanese girl born after World War II, say, in 1949, the year of Late Spring. She would likely have spent her entire time in elementary, middle, and high school in the presence of boys. She might have taken part in the newly-invented Japanese custom of girls giving “love chocolates” to boys on Valentine’s Day. She might have had a steady boyfriend, gone on dates with him, and even kissed him.

She would have been quite aware of the growing popularity of love marriages. If she entered into a marriage in the early to mid-1970s (perhaps after attending university and then being employed for a few years), it would have been more likely to be a love marriage than an arranged marriage. (The crossover point between the two S-curves was around 1967.)

Given this life experience, would it be any wonder that the idea of an S relationship would have seemed to her like something from the distant prewar past and Class S literature of little or no appeal to her? She would likely have been much more interested in the emerging genre of shōjo manga targeted to her and her contemporaries and perhaps even have dreamed of becoming a shōjo manga artist herself. But that’s a topic for the next chapter.

-

Erica Friedman, “On Defining Yuri.” In “Queer Female Fandom,” edited by Julie Levin Russo and Eve Ng, special issue, Transformative Works and Cultures 24, https://journal.transformativeworks.org/index.php/twc/article/view/831/835. ↩

-

Erica Friedman, By Your Side: The First 100 Years of Yuri Manga and Anime (Vista, CA: Journey Press, 2022). ↩

-

Verena Maser, “Beautiful and Innocent: Female Same-Sex Intimacy in the Japanese Yuri Genre.” PhD diss., Universität Trier, 2015. https://ubt.opus.hbz-nrw.de/frontdoor/index/index/docId/695. ↩

-

Shamoon, Passionate Friendship, 84. ↩

-

Again my argument echoes that of Yukari Fujimoto: “One explanation that I might give [for the absence of lesbians in shōjo manga] is that the closed, girls-only time and space that comprised Yoshiya Nobuko’s world does not exist as a communal object any more.” Fujimoto, “Where Is My Place in the World?,” 26. ↩

-

Joseph C. Trainor, Educational Reform in Occupied Japan: Trainor’s Memoir (Tokyo: Meisei University Press, 1983), 148. ↩

-

Mark McLelland, Love, Sex, and Democracy in Japan during the American Occupation (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), chap. 1, Kindle. ↩

-

McLelland, Love, Sex, and Democracy in Japan, chap. 4. ↩

-

National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, “Marriage Process and Fertility of Japanese Married Couples / Attitudes toward Marriage and Family among Japanese Singles: Highlights of the Survey Results on Married Couples/ Singles” (Tokyo: National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, 2017), 12, https://www.ipss.go.jp/ps-doukou/e/doukou15/Nfs15R_points_eng.pdf. ↩

-

The earliest figures leave many marriages unaccounted for (15 percent or so). That may be due to people not recalling exactly how they met their spouse or not being sure how to categorize the meeting. Also, the survey results likely understate the extent to which marriages were informally arranged by others acting as matchmakers, for example, by corporate managers acting on behalf of their employees. ↩

-

Late Spring, directed by Yasujirō Ozu (1949; New York: Criterion Collection, 2012), 1 hr., 48 min., Blu-ray Disc, 1080p HD. ↩

-

Like other films at the time, Late Spring was censored by the American occupation authorities. They rejected explicit mentions of arranged marriage as a feudal relic. Mars-Jones, Noriko Smiling, 190–91. ↩

-

Ozu included in this scene images referencing American military and cultural power: a sign in English on a bridge marking its “30 Ton Capacity” for drivers of tanks and other military vehicles, and a second sign in English encouraging consumers to “Drink Coca-Cola.” Late Spring, 22:56. ↩

-

Equinox Flower, directed by Yasujirō Ozu, in Eclipse Series 3: Late Ozu (Early Spring / Tokyo Twilight / Equinox Flower / Late Autumn / The End of Summer) (1958; New York: Criterion Collection, 2007), 1 hr., 58 min., DVD. ↩